The economic consequences in Angola of the Ukraine war

It is a fact that the war in Ukraine is affecting the entire world economy, and, certainly, this impact will also have political consequences[1], as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) immediately recognized.

The question that will be addressed in this report is about the specific impact of the war on the Angolan economy, which, as we know, is undergoing a demanding reform period and is about to emerge from a deep crisis. It will also superficially assess whether the economic impacts will have political influence.

The two faces of the impact of the oil price in Angola

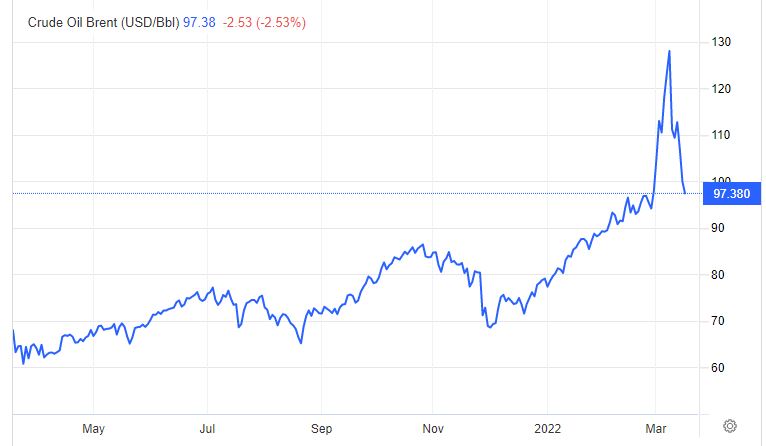

Naturally, the first impact in Angola refers to the price of oil. The rise in the price of oil was a trend that had been going on for some time and was accentuated with the outbreak of the war. To some extent, it is not a novelty brought about by the Ukrainian crisis, but a direction that has been underway for months.

On January 31, 2022, the price of a barrel of Brent was USD 89.9, on February 14, 2022, the value was USD 99.2. It is a fact that with the beginning of the war it reached USD 129.3 on March 8. At this point (March 16), it stabilized at USD 99.11. It seems that the equilibrium price of oil in the near future will be between USD 95-100, with, obviously, the possibility of shocks that make it rise or fall abruptly.

Fig. nº 1- Daily Chart of the Price of a Barrel of Brent (May 2021-March 2022)

Source: Trading Economics.com

In relation to Angola, we have to start from the budgeted forecast for 2022, which calculated the price of a barrel at USD 59. Therefore, there will be an added value since the beginning of the year corresponding to a minimum of 50% more. In this sense, as the budget was balanced, it means that there will be a financial surplus, which is obviously good news.

This rise in the price of oil therefore has, in the first place, two positive effects for Angola.

The first is at the level of extraordinary Treasury revenue, which will naturally increase. In simple terms, it can be said that there will be more money available from the state.

The second effect, which is already being felt, is the so-called “feel good factor” (or confidence index). Entrepreneurs and families are rethinking their expectations in a more positive direction, hoping for better signs from the economy. According to the Angolan National Statistics Institute, businesspeople are finally optimistic about the short-term prospects of the national economy, after remaining pessimistic for more than 6 years[2]. The rise in the price of oil is not the only reason for the optimism revealed, but it helps.

Note, however, that oil price gains do not translate directly into a positive budget balance. There are several constraints in translating the rise in oil prices into direct budgetary benefits for Angola.

The first of these is the type of relationship with China. China is the main buyer of Angolan oil. We do not know how the contracts are made and whether they automatically reflect price fluctuations. In the past, some intermediaries in the purchases and sales of oil to China even entered into fixed-price contracts that greatly harmed the Angolan Treasury[3]. It is imagined that such “schemes” no longer exist, but there are no certainties. What is certain is that, probably, the contracts between Angola and China regarding oil will contain some type of “dampers” that will imply that there is no direct impact on prices. Furthermore, some oil experts, such as those at Chatham House, believe that the fact that China buys around 2/3 of Angolan oil (actually 70%[4]) allows it a certain monopolistic control of the price, meaning that Chinese purchases are made in order to lessen price rises, undermining Angolan advantages[5].

Second, we have debt service. Apparently, there are contractual mechanisms that imply that a higher price of oil implies an increase in debt service, that is, in payments to be made. The Minister of Finance, Vera Daves, has already acknowledged that “what results from the price increase cannot be made an arithmetic account with production” and that the price of a barrel of oil, above one hundred dollars, forces Angola to pay more to their international creditors[6].

Furthermore, the rise in the price of oil also has a possible negative effect on the Angolan budget, which refers to the price of fuel sold to the public. As is well known, this price is subsidized by the State; to that extent, if the cost of oil increases and the government does not increase fuel, it means that it will have to bear more subsidies and spend more to maintain fuel prices. If you don’t, you could be fueling inflation, which is no longer low in Angola, and creating social problems and discontent.

There are four factors here: price increase, relations with China, increase in debt payment obligations and increase in fuel subsidy that have to be taken into account to assess the real impact of the rise in oil prices on the accounts and the Angolan economy.

In fact, we do not have precise figures on these impacts, only ideas of magnitude, and in view of these, the conclusion that can be drawn is that a 50% increase in the price of oil in relation to what is foreseen in the Budget leaves a treasury slack that is still accentuated after the increase in debt service payments and support for the rise in fuel prices, and it is undoubted that a financial “cushion” will be created.

The question of food prices

Alongside the price of oil, many other commodity classes are rising in price. One of them is cereals, namely wheat.

Ukraine and Russia together account for a quarter of all world wheat exports. The conflict is dramatically driving up wheat prices. With the start of the war, the price of a bushel of wheat rose to $12.94, 50% more expensive than at the beginning of 2022.

In the midst of a war, it is unclear whether Ukraine’s farmers will be willing to spend whatever capital they have to plant the next harvest, or even if they will be in a position to do so. What is certain is that Ukraine has announced a ban on all exports of wheat, oats and other staple foods to avoid a massive food emergency within its borders. Therefore, wheat exports from Ukraine, even if there is production, are compromised.

Unlike oil, which affects prices almost immediately, grain prices take weeks, if not months, to reach consumers. In reality, raw grain needs to be shipped to processing facilities to make bread and other staples – and that takes time. In this sense, possibly, it will not be an immediate crisis for Angola, but it will reach the country.

According to government sources, Angola is self-sufficient in six basic agricultural products: cassava, sweet potato, banana, pineapple, eggs and goat meat. However, wheat is the most imported commodity, accounting for 11%[7]. Let us recall that wheat is an essential element in the diet of Angolans, which a few months ago led the Minister of Industry and Commerce to suggest replacing bread with cassava, sweet potatoes, roasted bananas and “ginguba” (peanuts). This statement has generated much criticism. However, from the strict point of economic self-sufficiency it may make sense, since possibly the price of bread will rise and eventually the price of national goods may fall, if there is an adequate competitive market.

What is certain is that Angola could be in the same danger as Egypt, an extremely wheat-based crop that suffers social upheaval when the price of wheat rises.

When grain prices soared in 2007-2008, bread prices in Egypt rose by 37%. With unemployment on the rise, more people became dependent on subsidized bread – but the government didn’t react. Annual food inflation in Egypt continued and reached 18.9% before the fall of President Mubarak.

Most of the poor in these countries do not have access to social safety nets. Bread images became central to the Egyptian protests that led to Mubarak’s downfall. Although the Arab revolutions were united under the slogan “the people want to overthrow the regime” and not “the people want more bread”, food was a catalyst. Incidentally, it should be noted that “bread riots” have been occurring regularly since the mid-1980s, usually after the implementation of policies “advised” by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Angola is not Egypt, but it is essential that the government pay close attention to the evolution of wheat and bread price to avoid social unrest, at a stage when it begins to emerge from the prolonged crisis.

However, as in the case of oil, there is another side, and in this case it is positive. The crisis in agricultural production resulting from the war could be a turning point for foreign investors to invest in agriculture in Angola. Angola is one of the countries in the world with the most potential, as we have already mentioned in a previous report[8], so this may be the time of opportunity for investors to see Angola’s agricultural capacity and take advantage of it. One of the most promising sectors with the most potential is agriculture. There is currently a combination of factors that make it one of the most profitable bets for investment in Angola.

Conclusions and recommendations

The war in Ukraine has several impacts on the Angolan economy.

The rise in the price of oil, not bringing directly proportional revenues, creates a “cushion” in the Treasury and a “feel good factor” in the business community, which could be a growth booster.

The rise in the price of cereals, especially wheat, can create serious inflationary pressures and discontent among the population, a situation for which the government must be aware. At the same time, it will draw attention to the enormous investment potential that Angola has as an agricultural country.

The government should create a special reserve derived from the gains from oil to guarantee the supply of cereals to the poorer sections of the population and also to promote agricultural investment in Angola.

[1] https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2022/03/05/pr2261-imf-staff-statement-on-the-economic-impact-of-war-in-ukraine

[2] https://www.angonoticias.com/Artigos/item/70611/optimismo-regressa-no-seio-dos-empresarios-seis-anos-depois

[3] Rui Verde, Angola at the Crossroads. Between Kleptocracy and Development (2021), p. 24.

[4] https://www.forumchinaplp.org.mo/pt/china-foi-o-destino-de-71-do-petroleo-exportado-por-angola-em-2020/

[5] Explanations given at a Chatham House meeting that we replicate here, respecting the house rules.

[6] https://rna.ao/rna.ao/2022/03/03/preco-do-petroleo-a-cima-dos-cem-dolares-obriga-governo-angolano-a-pagar-mais-aos-credores/

[7] https://www.expansao.co.ao/economia/interior/grupo-carrinho-destaca-se-nas-importacoes-e-exportacoes-do-pais-106709.html

[8] https://www.cedesa.pt/2020/06/15/plano-agro-pecuario-de-angola-diversificar-para-o-novo-petroleo-de-angola/