The electoral system of Local Authorities in Angola and the inclusion of Traditional Power

Rui Verde

Previous note:

Having been invited and accepted to participate in the 1st Angolan Congress on Electoral Law, to be held on December 7 and 8, 2023, for technical reasons I was unable to present my paper online. Here is the text of the presentation.

Specificity of local elections

A local electoral system does not necessarily have to replicate the national system. Although in both cases we are dealing with the choice of representatives in democratic processes, the nature of the elections and bodies is somewhat different.

In many countries, the abstention rate in local elections is higher than in national elections[1] , and local governance is dedicated to issues that are often different from national issues. To a certain extent, although this is disputable, especially in politically polarized countries like Angola, it is understood that local politics will be essentially non-ideological. In the United States, for many years, academics argued that there was little difference between the policies of locally elected officials from the Democratic or Republican parties because most local political issues were technical and non-political. As Adrian wrote, “there is no Republican way to pave a street and no Democratic way to install a sewer.”[2] It should also be noted that the issue of representation of various minorities and interests is particularly acute at the local level.[3]

It is this structural differentiation that serves as the starting point for a short commentary on the current electoral system for local authorities in Angola, addressing two specific issues. Firstly, there will be a brief description of the current constitutional-legal model for local elections, and secondly, a brief reflection on the role of traditional power, given the undeniable demographic pressure in Angola.

Local power in the Constitution

The first place to look at local power in the Angolan legal system is the Constitution (CRA), which deals with the subject in Articles 213 et seq.

It states that the “organizational forms of Local Power include Local Authorities, the institutions of Traditional Power” (art. 213, no. 2) and that Local Authorities “have, among others and under the terms of the law, the following powersº 2) and that Local Authorities “have, among others and under the terms of the law, powers in the areas of education, health, energy, water, rural and urban equipment, heritage, culture and science, transport and communications, leisure and sports, housing, social action, civil protection, environment and basic sanitation, consumer protection, promotion of economic and social development, land use planning, municipal police, decentralized cooperation and twinning.” (art. 219), with various bodies such as an “Assembly with deliberative powers, a Collegiate Executive Body and a Mayor” (art. 220, no. 1).

In terms of the electoral system, the Constitution establishes that the “Assembly is made up of local representatives, elected by universal, equal, free, direct, secret and periodic suffrage of the electors in the area of the respective municipality, according to the proportional representation system.” (art. 220, no. 2), the “Collegiate Executive Body is made up of its President and Secretaries appointed by it, all accountable to the Municipal Assembly.” (article 220, no. 3) and the President of the Executive Body of the Municipality is the head of the list with the most votes for the Assembly (article 220, no. 4). Finally, Article 220(5) states that “candidacies for elections to local authority bodies may be presented by political parties, alone or in coalition, or by groups of voting citizens, under the terms of the law.”

Regarding the institutions of traditional power, the Constitution recognizes them in its articles 223 and following, referring to customary law for their designation, and to the law for their articulation with Local Authorities (article 225).

Consequently, according to the Constitution, there are two forms of local power, local authorities and traditional power, the relationship between which is not established in the fundamental law. In the case of local authorities, their method of election is defined from the outset, which is not the case, of course, with traditional power.

The electoral system of local authorities

In order to describe the electoral system envisaged for Local Authorities, in addition to the Constitution, the Organic Law on the Organization and Functioning of Local Authorities (Law no. 27/19 of 25 September) must be added, as well as the Organic Law on Local Elections (Law no. 3/20 of 27 January), which we will stick to in this description.

As mentioned, there are three bodies in municipalities: the assembly, the executive and the mayor. Looking at the municipality, the local authority par excellence (article 218 of the CRA), we see that only two of these bodies, the assembly and the mayor, are elected. The executive is appointed by the mayor. In fact, Article 29(2) of the Law on the Organization and Functioning of Local Authorities states that the Municipal Council (the executive) is made up of Secretaries appointed by the Mayor, although they are accountable to the Municipal Assembly. The removal of Secretaries is the responsibility of the Mayor (Article 31(1)(b)).

In municipalities, there are two elective bodies, and we’ll focus on them. These are the Municipal Assembly and the Mayor.

The members of the elective bodies are elected by universal, equal, direct, secret and periodic suffrage by the citizens residing in the local district (article 15 of the Municipal Elections Law – LEA). The most relevant article of the LEA is Article 40, which defines the single-list electoral model for the Assembly and the Mayor’s Office, replicating the national constitutional model that has raised so much controversy. In fact, under the terms of this regulation there will only be one list. Article 40 of the LEA states that candidacies for Mayor are presented in the context of the presentation of lists of candidates for members of the Local Authority Assembly (Article 40(1)), and that the candidate for Mayor is the one who appears first on the list of candidates for member of the Assembly (Article 41(2)). Accordingly, each ballot paper will bear the name of the competing party, coalition or group of citizens, the name of the candidate for mayor and the respective passport photo, the acronym and symbols of the candidacy (Article 17 of the LEA). The person on the list with the highest number of votes, even if not an absolute majority, will be elected Mayor, and will have the right to appoint the entire executive (article 21 of the LEA). The members of the Municipal Assembly are elected according to the proportional representation system, following the d’Hondt method for converting votes into mandates in accordance with the rules of article 29 of the LEA.

It should be noted that this electoral system, as well as the rules regarding the ballot paper, have already been upheld constitutionally by Ruling 111/2010 of the Constitutional Court when it considered the text that became known as the 2010 Constitution.

So we have a mixture of the one-round majority system that elects the mayor and the proportional system that determines the composition of the municipal assembly.

It will be argued in its defense that it simultaneously guarantees the efficiency of the government (one-round majority system) with broad democracy (proportional system for the constitution of the Assembly).

But it could also be said that it retains the “defect” of a not entirely direct election of the President, which many in the CRA criticize with reference to the election of the President of the Republic.

Also for those who like Portuguese comparatistics, it should be noted that it does not follow the Portuguese model in which the election of the Mayor is separate from the election of the Municipal Assembly, and a party can win the Presidency and lose the Assembly as is currently the case in Lisbon, in addition to the fact that the executive (Council) is formed according to the electoral results, depending on the presidential will only the distribution or not of portfolios[4] .

In this respect, the Portuguese model could be educational, as it would teach the various parties, which are usually polarized, to enter into local government agreements, which would be a basis for a good democratic spirit of dialogue and tolerance.

As an innovative reference, it should be mentioned that groups of voting citizens can, without any authorization, stand in municipal elections (art. 44 of the LEA) provided that they are at least 150 voting citizens in the respective constituency (art. 48, no. 1 of the LEA).

Traditional power and demographic expansion

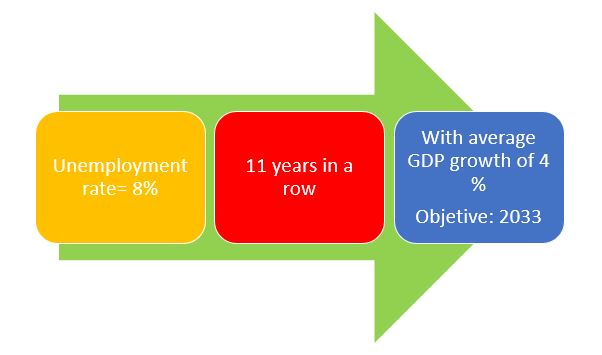

It is a fact that Angola’s demography has undergone an explosion. “Between 1960 and 2020, Angola’s population grew 6.2 times, reaching more than 30 million inhabitants, a more significant increase than that seen in sub-Saharan African countries (5.1x) and than in other regions such as East Asia (2.3x) and Latin America (2.9x).”[5]

It is clear that this number of inhabitants is not in line with the current number of Angolan municipalities, 164. Just remember that Portugal, with 10 million inhabitants, has 308 municipalities.

While it is true that the current number of municipalities in Angola does not correspond to the real needs of the population, it is also true that the idea of increasing the number from 164 to 581 is absurdly impossible, both for financial reasons and for administrative and bureaucratic reasons.[6]

We therefore need to look for innovative, possible and constitutional responses. It is in this sense that the constitutional system is relevant, placing the institutions of traditional power under the heading of local power, which also includes local authorities. The same is true of the Organic Law on Local Power, Law 15/17 of August 8, which deals with Local Authorities and Institutions of Traditional Power.

The constitutional and legal system outlines a start on answering the question we posed above. To the systematics we have to add some considerations about the current paradigm of law. We can no longer think of law in terms of the positive rational frameworks of the 18th and 19th centuries, which apply a single menu to all the regulation of social life. Without delving into the subject here, we have to consider law as an open system[7] that allows for various material intersections and contributions and not just a closed, single and reductive positivism. It is in this context that it is important to allow the institutions of traditional power to take on the role of local authority where these do not exist and are necessary.

The reality is that there are two types of Local Authorities in force, those regulated by positive law and those derived from customary law and regulated by custom, accepting a plurality of regimes, legal and customary[8] , with a view to the effective implementation of decentralized local power close to the population, accepting the “presence of more than one normative order in a social field.” [9]

In essence, it is a question of realizing a systematic desire of the Constitution, which, by placing both formal Local Authorities and Local Power Institutions under the aegis of Local Power, is not making a mistake, as some claim, but is opening up avenues for the consideration of a true legal pluralism in Angola, which will act as a solution to problems linked to the efficiency of the state machine.

[1] Anzia SF. 2013. Timing and Turnout: How Off-Cycle Elections Favor Organized Groups. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press or Hajnal ZL. 2009. America’s Uneven Democracy: Race, Turnout, and Representation in City Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

[2] Adrian CR. 1952. Some general characteristics of nonpartisan elections. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 46: 766-786, p. 766.

[3] Abott, Carolyn, and Asya Magazinnik. “At-Large Elections and Minority Representation in Local Government.” American Journal of Political Science 64, no. 3 (2020): 717-33.

[4] Law no. 75/2013, of September 12th

[5] Economic Studies Group (2023), Demographic transition in Angola: burden or bonus? MakaAngola, https://www.makaangola.org/2023/07/transicao-demografica-em-angola-onus-ou-bonus/

[6] Verde, Rui, (2022), The “(ir)rational” of the 581 municipalities, MakaAngola, https://www.makaangola.org/?s=munic%C3%ADpios

[7] Viehweg, T. Topik und Jurisprudenz, 1954; Perelman, Ch. Das Reich der Rhetorik; Rhetorik und Argumentation, 1980

[8] Cfr. Feijó, Carlos, A coexistência normativa entre o Estado e as Autoridades Tradicionais na Ordem

Angolan Plural Law, Coimbra, Almedina, 2012.

[9] Fernandes, T. 2009. Local power in Mozambique. Decentralization, legal pluralism and legitimacy. Porto, Edições Afrontamento, p. 40