In search of a new paradigm for Angola-China relations

Overcoming the debt issue

Apparently, João Lourenço is due to visit China soon, and Beijing already has an ambassador in Luanda again. So, there are marked dynamic movements in the Angola-China relationship.

It’s not the Angolan President’s first visit to Beijing, but it is the first after his public and effective rapprochement with the United States, and at a time when the issue of debt to China has become the main aspect of relations between the two countries.

With regard to debt, there is one indisputable fact. Angola has made a substantial reduction in its capital debt since 2017. In fact, in that year the amount of capital owed was 23.204,9 billion dollars, while at the end of 2023 it only stood at 17.921,0 billion US dollars, a reduction of exactly 5.283,9 billion dollars according to official figures from the National Bank of Angola (BNA), in capital alone, not including interest.[1] This means that even during years of crisis – don’t forget that the Angolan economy contracted between 2016 and 2020[2] – the Angolan state was able and willing to pay its debt to China.

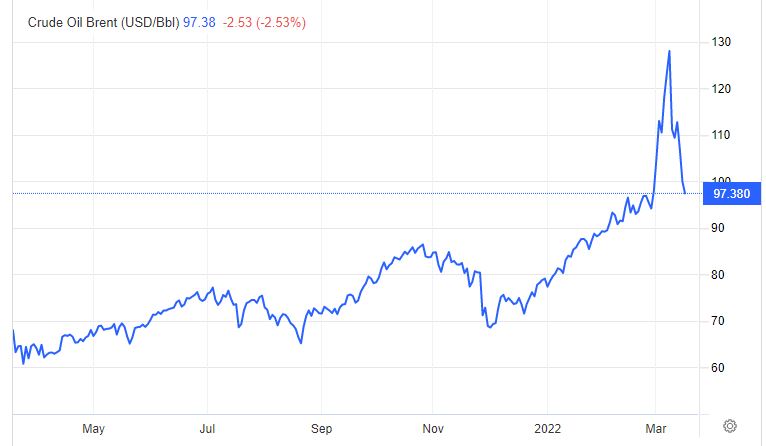

So the question is not one of capacity, but one of sacrifice, or rather opportunity cost. The capital taken from the state budget to pay China is capital that is not used in other sectors, such as human development, education, health, sanitation, etc. In addition, of course, the budgetary instability caused by fluctuating oil prices always puts great pressure on the treasury’s liquidity to meet payments.

It is for this reason, and after the great Angolan effort of more than 5 billion dollars made during João Lourenço’s presidency, that this should be the time to decompress in the payment of the debt to China.

In addition to this, there is another fact, which has already been dealt with sufficiently[3] , which is the so-called “odious debt”. It now appears that a large part of the debt Angola contracted from China ended up illegally in the hands of private Angolan entities that did not use the funds for the common good, but for their own undue profit. Recent reports indicate that the entire mechanism for embezzling funds was structured with the participation of Chinese entities mandated by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party[4] . If confirmed, and it has not been duly certified, this action places the amounts of “odious debt” in a separate category, which should be the subject of separate negotiation by the diplomacies of the two countries, so as not to give rise to any proceedings in an arbitration court, as is provided for in the bilateral financing agreements.

Once the issue of debt has been framed, it is clear that now is the time to move beyond debt and create a new paradigm for relations between Angola and China

The new paradigm between Angola and China: emptying the China-US Manichaeism

It could be thought that João Lourenço’s rapprochement with Joe Biden, promoting an effective strengthening of Angola’s relations with the United States, would lead to a necessary estrangement and distancing from China.

We don’t share that view. On the contrary, it is understood that the Manichean vision that supports this view is not supported by facts.

Firstly, in the economic sphere, despite the American rhetoric that began with the Trump administration and continued with Biden, what is certain is that relations between the two countries – the US and China – remain intense. American companies – and Western companies in general – are still very dependent on Chinese markets and production chains. The more aggressive rhetoric has only benefited a few intermediary countries that receive Chinese investment and then export the products resulting from that investment to the US with a “non-Chinese label”, and in the end the ties remain strong. In this sense, for example, Tesla’s Elon Musk is inviting Chinese suppliers of parts for his cars to replicate their production chains from China to Mexico[5] . Recently, the CEO of Apple – Tim Cook – met with Chinese officials and reaffirmed his commitment to the Chinese market and his desire to forge closer ties with the Beijing government[6] . Another current example is ExxonMobil, the American energy giant that plans to invest in a multi-billion dollar petrochemical complex in Guangdong province[7] . In fact, if everything goes according to plan, the project, which has a total investment of 10 billion dollars, will have its first phase completed before the end of the year. Not to mention Starbucks, the American multinational, which now has more than 6,800 shops in China alone, and which in 2023 invested more than 200 million dollars in a new campus in China, a sign of how crucial the Chinese consumer continues to be for the global coffee chain, despite a certain economic slowdown .[8]

In addition, the success of the Lobito Corridor, on which both Angola and the United States are betting, necessarily requires Chinese competition – which dominates the bulk of the raw materials – in order to be successful.

These real facts about the economic infrastructure point to a necessary triangulation between intermediary countries, China and the United States, which translates into an ideal role for Angola, which is rightly positioned as a “bridge” between Asia and the West. This reciprocal rapprochement can therefore be beneficial rather than disadvantageous, if Angola takes advantage of its role as a hinge in a skillful and intelligent way.

The new paradigm between Angola and China: exchanging loans for productive investment

The essential fact is the need for a paradigm shift. Angola cannot sustain its treasury and development on loans that have to be paid back. This doesn’t mean that it won’t use them and resort to them when it needs to, but the strategy has to be different, and different means investment. What we want from China is investment, not more loans.

Let’s look at China’s policy in Portugal. There, China essentially makes investments, buys shares in companies and becomes a partner in others. It brings capital to Lisbon to invest in the production process, not to earn interest. The main Chinese investments in Portugal are concentrated in sectors such as banking, energy and insurance. Take the case of EDP. Chinese investment in EDP – Energias de Portugal, S.A. is significant. China Three Gorges (CTG) has been EDP’s largest shareholder since 2011. Last year, the shares held by CGT were valued at 4,634 million euros[9] . In the health sector, the Chinese private group Fosun stands out as the largest shareholder in the Luz Saúde Group. This group, which is one of Portugal’s leading healthcare organizations, is controlled by the Chinese Fosun and the insurance company Fidelidade (which, in turn, also has the Chinese Fosun as a shareholder)[10] . The group currently manages 30 hospitals, clinics and health centres. In 2022, its operating profits totaled 600 million euros, up 11 % on the previous year[11] .

In 2023, Portugal attracted more foreign industrial investment and the largest came from China.[12] This is “the Chinese electric car battery factory CALB, which has already started the environmental licensing process for a new plant in Sines, a project worth 2060 million euros, for which 90 hectares of land have been set aside and 1800 jobs have been promised[13] “.

This is the kind of relationship that Angola should begin to have with China. Not a relationship of dependence on loans, but of direct Chinese investment in the Angolan economy.

There are several areas for Chinese investment in Angola, but we would highlight the possibilities of car factories, given the huge increase in this industry in China and the fact that it is becoming the largest in the world. Equally important is the telecommunications and electricity sector, which is so lacking in Angola. Another sector to invest in could be textiles, after the failure of Ethiopia, shortening the logistical supply lines to the US and Europe in relation to Vietnam.

Other hypotheses should be studied, but here are some suggestions for Chinese investment in Angola: creating a cluster in the automobile industry, telecommunications and electricity, textiles.

[1] PUBLIC EXTERNAL DEBT BY COUNTRY (STOCK): 2009 – 2023, https://www.bna.ao/#/pt/estatisticas/estatisticas-externas/dados-anuais

[2] https://pt.countryeconomy.com/governo/pib/angola

[3] Rui Verde, 2023, O tratamento jurídico a conferir à dívida pública angolana à China que resulta de apropriação privada, Communication to the III International Congress of Angolanistics

Biblioteca Nacional /Lisboa

[4] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/sam-pa-ccp-02062024151947.html

[5] https://oglobo.globo.com/economia/noticia/2024/02/16/elon-musk-atrai-fornecedores-chineses-para-se-instalarem-bem-ao-lado-dos-eua.ghtml

[6] https://www.adrenaline.com.br/hardware/ceo-da-apple-reafirma-seu-compromisso-com-a-china/

[7] https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202402/1307530.shtml

[8] https://edition.cnn.com/2023/09/19/business-food/starbucks-china-coffee-center-intl-hnk/index.html

[9] Idem.

[10] https://observador.pt/2020/10/21/luz-saude-dos-chineses-da-fosun-foi-quem-fez-mais-negocios-com-o-estado-na-pandemia/

[11] https://jornaleconomico.sapo.pt/noticias/luz-saude-tem-dimensao-para-entrar-no-psi-diz-lider-da-bolsa-nacional/

[12] https://www.publico.pt/2024/03/03/economia/noticia/portugal-captou-investimento-estrangeiro-industrial-maior-veio-china-2082344

[13] Idem.