João Lourenço’s macroeconomic achievements and the problem of youth unemployment: a financing proposal

The recent macroeconomic achievements of the João Lourenço government

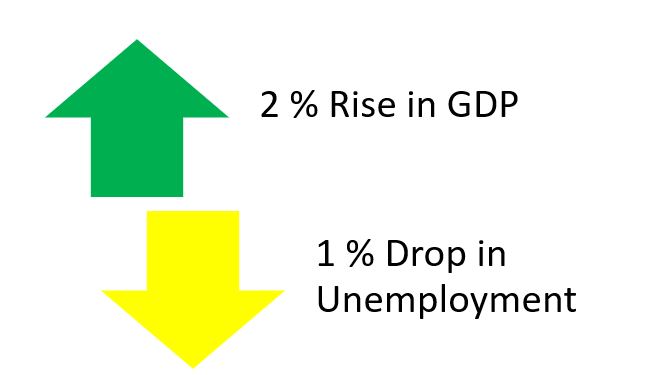

After years of crisis, recession and almost economic despair, which, of course, translate into the electoral results of the past August and the constant unrest of social networks, the Angolan government has a very encouraging macroeconomic framework.

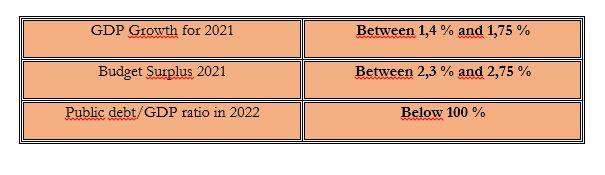

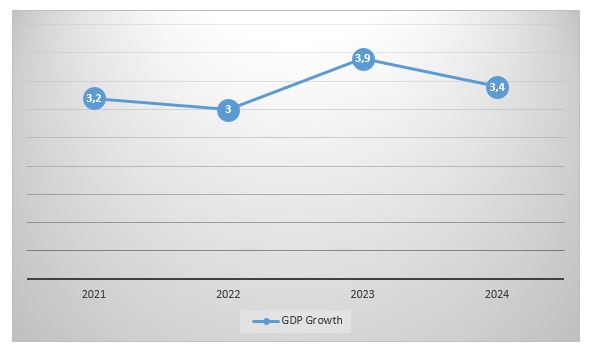

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth designed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to 2023 is 3,5%, a robust number[1], mainly, bearing in mind that the country has been in recession since 2016, with a peak negative in 2020 of -5.6%.

The recent predictions of the IMF foreign debt point to a 63.3% ratio of GDP. Once again, it should be noted that by 2020, this ratio corresponded to 138.9% of GDP. There are several factors that explain this fall, some nominal, but it is impressive.

In turn, the state’s general budget for 2023 has a global surplus tax balance of 0.9% of GDP, and proposes to create a positive primary balance in the order of 4.9% of GDP.

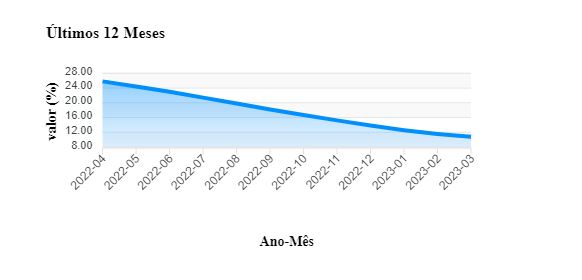

In inflation, the homologous variation of March 2023 is 10.81%[2], demonstrating a fast and consistent drop.

Fig. No. 1-decreasing inflation (source: BNA)

Consequently, there is no doubt that the Angolan economy has changed since 2016, and from an uncontrolled country and on the brink of bankruptcy, we have a healthy macroeconomic situation.

Youth unemployment: a serious and persistent problem

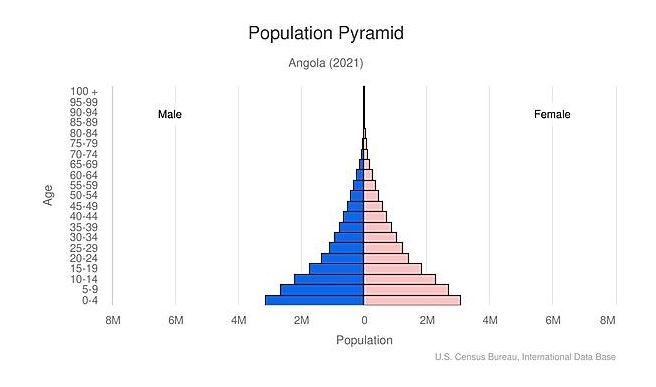

Despite the good news in the macroeconomic front, the population still looks alien to success and popular feeling is not corresponding to the numbers.

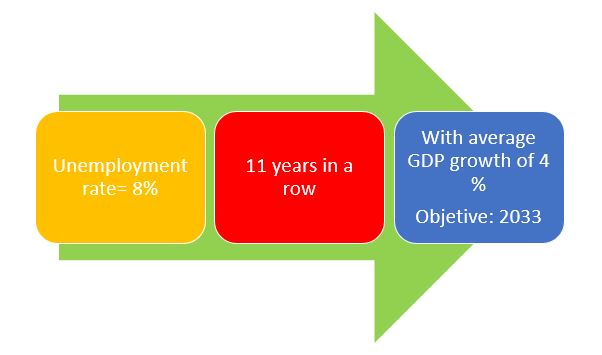

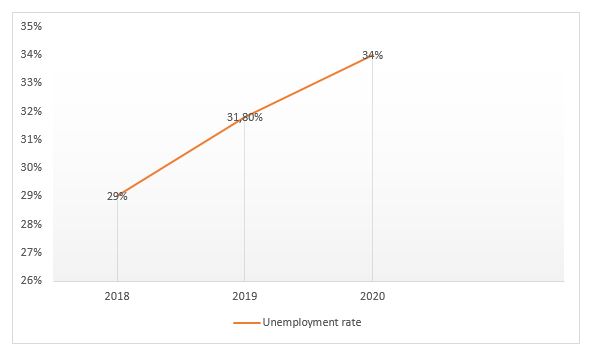

An explanation for such a phenomenon is the persistence of high unemployment, especially youth unemployment. According to the Instituto Nacional de Estatísticas(INEA) in the IV quarter of 2022, the total unemployment rate was 29.6%, which represented a slight drop from previous quarters, but meaningless.

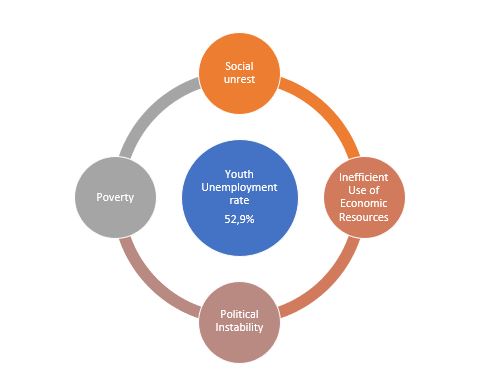

In relation to the young population (between 15-24 years) the unemployment rate is 52.9%[3].

This number is not acceptable and there is no economy that can be considered healthy as long as such a phenomenon persists.

The consequences of a high unemployment rate are known and are numbered here. It is a waste of resources, showing that the economy is not working at its potential level, but in an inefficient way. Of course, it is a situation that has the potential to generate an increase in poverty and also social unrest.

Certainly, a good part of the social unrest that exists in Angola, whether on the streets or on social networks, directly and inappropriately results from youth unemployment. Therefore, the consequences are extremely and inappropriately negative.

Fig. No. 2- Consequences of the high youth unemployment rate in Angola

Youth unemployment: social resilience rate and dangerous systemic instability

From the constitutional order and stability of the state point of view, there is a systemic point for youth unemployment that must take into account and be underlined.

There will be a threshold where the unemployment rate becomes unbearable and leads people to political action to modify the situation, it will be a kind of trigger that gives rise to revolutions, subversions, regime changes, etc. We will call this a social rate of resilience to unemployment, as constituting the unemployment threshold that a society supports without revolt.

Therefore, the point is that a youth unemployment rate above 50%, in an essentially young country and with an expansive demographic growth rate, is an explosive rate and may be very close to the social resilience rate. This means that the present rate of youth unemployment is perhaps the largest factor of political destabilization of Angola and has the potential of overthrowing constitutional orders and crying out by elements of extra-legal action.

It is at this time “that fighting unemployment becomes the priority of priorities. … When the threshold of tolerance to unemployment is reached, it is necessary to act quickly and in strength. Temporization serves nothing, nor does it serve to develop an apology speech based on economic difficulties.[4]”

It is never too much to note that Hitler’s rise to power and his subsequent popularity in the 1930s with the German people was due to unemployment and the solution he gave to the problem. German unemployment dictated the fall of the Weimar Republic in Germany and the establishment of the Nazi dictatorship. Unemployment is the provocative of extremism and agitations, superior to any other.

Therefore, it is considered that in the present Angolan economic state, the fight against youth unemployment has become the priority of priorities.

Fighting Youth Unemployment and Financing: The Autonomous Financial Instrument (AFI)

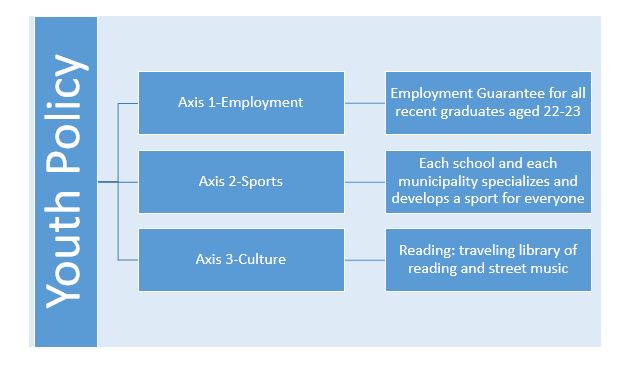

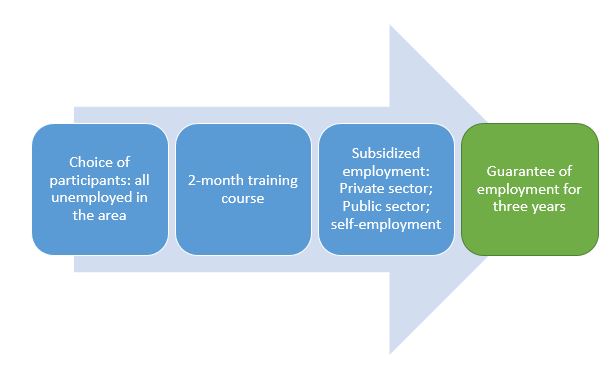

It is evident that the Angolan private economy does not have the ability at this time to create the jobs needed to make the unemployment rate of its crisis threshold. It is obvious that mass intervention of the state is necessary to create employment to an acceptable social level.

State programs must be traditional, based on the massive construction of infrastructure, roads, ports, and strategic industry, as well as in specialized technical training and sending young people to several provinces for social support tasks in the area of basic sanitation, housing, primary health and agriculture.

They do not serve the palliatives that market economies adopt in these situations: unemployment allowance, internships, vocational training for conversion, tax benefits. These policies only work in the face of short oscillations of supply and job search curves, they do not operate in structural and permanent unemployment situations.

The fight against youth unemployment has to be the object of a massive national program with rapid effects that leads into employment offer to several million young people.

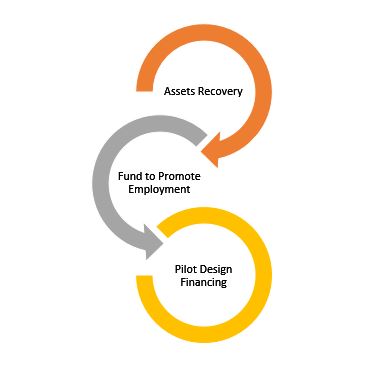

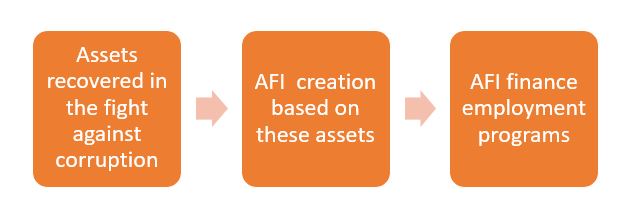

Classic economists will counteract that the state has no funds for such comprehensive and massive programs. It is at this time of reasoning that the fight against corruption comes in. According to figures now presented, “Angola recovered six billion dollars and seized another 21 billion in the context of the asset confiscation, half of which abroad[5]. It is not known exactly how much of these values are merely provisional seizures and how many are already available to the state. The truth is that they are appreciable amounts.

The concept that proposes to finance mass programs against youth unemployment is simple: all youth employment financing programs will be funded by a mechanism outside classic credit, creating an exceptional vehicle based on seized assets.

Some of the assets seized, for example, up to an amount of $ 5 billion will serve as a capital or guarantee of an autonomous financial instrument (AFI) that will launch employment promotion programs. The financing of this program will be based on the seized assets and will be paid through securities issued by AFI.

AFI either will pay the programs directly with securities that issue based on seized assets or issues debt securities to raise funds for this payment. What is certain is that it would create money outside the classic system and thus allow to create hope for the unemployed, making the fundamental connection between the fight against corruption and the fight against unemployment, which we consider primordial.

Fig. n. º3- Simplified scheme of the financing of unemployment programs

Conclusions

Youth unemployment is the greatest threat to Angolan political stability. The theme must be seen and create massive state intervention mechanisms funded by an autonomous financial instrument supported by the assets seized in the fight against corruption.

AFI would pay employment programs with securities based on these actives.

[1] https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/AGO (accessed at 19th April 2023)

[2] https://www.bna.ao/#/pt (accessed at 19th April 2023)

[3] Folha de Informação Rápida _ Inquérito ao Emprego em Angola _ IV Trimestre 2022, (INEA 2023), p.9

[4] Jean-François Bouchard, O Banqueiro de Hitler, 2023, p. 2022.

[5] https://observador.pt/2023/04/18/angola-recuperou-6-mil-milhoes-em-dinheiro-e-apreendeu-mais-21-mil-milhoes-em-ativos/ (accessed at 19th April 2023)