The economic situation in Angola and Agenda 2050

Recent economic turmoil

The results of Angola’s economic policy, which had been favourably received by international institutions and public opinion in recent times, namely low inflation, fiscal consolidation, control of public debt and the success of foreign exchange liberalisation, seemed to suffer a blow in June.

The trigger for this change in perception was the abrupt announcement of the rise of more than 80% in the price of commercial petrol, due to the partial withdrawal of the state subsidy (without the necessary focus on the mitigation measures that had been well thought out), which was followed by a series of cascading events, the resignation of Manuel Nunes Júnior as Minister of State for Economic Coordination, some rumours about delayed public service salaries, and inevitably the announcement by a rating agency that Angola’s economic outlook had been downgraded from “positive” to “stable”.[1]In addition, the Kwanza is depreciating rapidly against the dollar and the euro. At the end of June, the Angolan national currency passed 800 kwanzas to the dollar for the first time.[2]

The depreciation of the kwanza has raised renewed fears of inflation, in a country still heavily dependent on imports for its daily life. Last February, the National Bank of Angola said that the country would spend over US$2 billion (1.8 billion euros) on food imports in 2022, representing a 40 percent increase over the previous year.[3] A lower value of the national currency and a rise in food import requirements obviously results in higher prices.

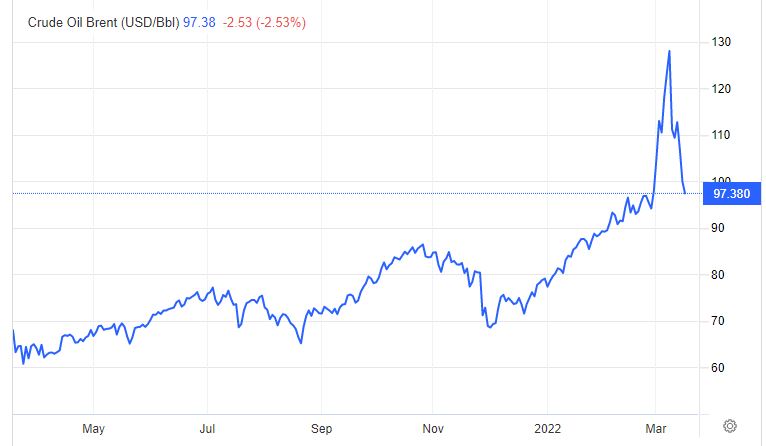

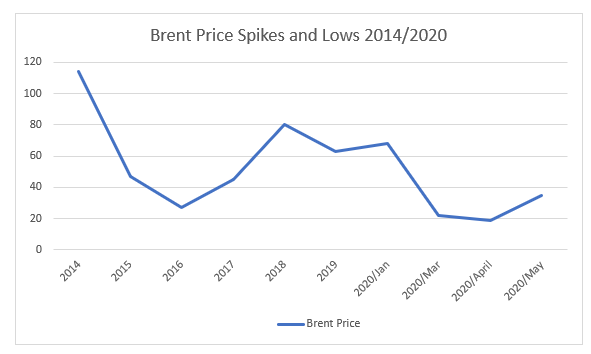

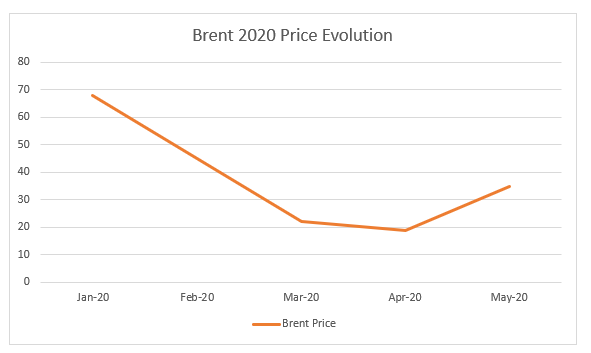

In turn, the statement that the new Minister of State and Economic Coordination made about the delays in some public salaries in May, did not reassure, since Lima Massano assured that this was due to “a time lag between the time of receipt of the funds resulting from tax collection and the period of payments.”[4] The minister’s explanation is not contested, the problem is that even if we accept it, it contains a problem, which is that of the government’s lack of cash reserves, indicating that the budgetary restraint imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has not created any space for Angolan public finances. It should be noted that although the price of oil is not very high, over the last six months it has fluctuated between USD 70 and 80, with prevalence at USD 75/76. As the State Budget was based on 75 USD (which we criticised at the time[5] ), the truth is that the price has been in line with the forecast, although with no margin for manoeuvre.

The possible effect of oil prices

In the light of the above, in theory, the price of oil will not yet have a negative effect on the State Budget in the immediate future.

However, this could happen in the second half of the year. We have formed the opinion that there is a strong downward pressure on the price resulting from the oil embargoes on Russia and probably Iran. Our thesis is that these Western oil embargoes do not have the effect of significantly restricting the supply of that product by Russia, which would push up the price of oil, but rather of selling it at a discount to intermediaries who act as “laundromats”. This means that the longer the oil embargo on Russia lasts, the more Russia will make the circumvention mechanisms efficient and the more it will sell oil at a discount. Thus, it is very possible that there will continue to be downward pressure on the price of oil, especially if China’s economy continues not to show the strength of the past.

Consequently, it may be that fiscal tightening will intensify in the second half of this year if oil prices succumb to these pressures.

The doctrinal and practical problem

The concrete fact is that IMF “recipes” in Angola seem to have failed, and once again the application of classical economic doctrines does not work.

It is increasingly clear that a universal theory of economics based on the classical thinking disseminated by North American universities may work in mature developed economies or in places with relatively solid institutions (market, government, courts), but it does not work in countries still suffering from extreme imbalances and under institutional construction. It cannot speak of true markets functioning freely according to the rules of supply and demand, nor of efficient governance or even of a justice system approaching that which works in Angola. For various reasons, these are unfinished processes in the making. To that extent, any economic model that takes them as preconditions will fail. That is why the IMF measures fail, failing to bring prosperity to Angola and making the country go from one crisis to another. It should be stressed that since 2009 the IMF has been monitoring and agreeing with Angola’s economic policies.

There is a doctrinal problem underlying the negative impact of economic policy in Angola that is linked to the fact that the main decision-makers are trained in foreign universities that adopt institutional models of the market economy, with greater or lesser state intervention, but always assuming that the situation is operating normally. The truth is that Angola is in a pre-institutional situation, so the models to be applied should be those of development and institutional building rather than stabilization. This problem, while seemingly very theoretical, has real practical relevance, since something is being applied that has little to do with reality.

Furthermore, some fundamental structural reforms were not undertaken by the government. A system marked by the interference of politicians in the running of companies was maintained, with continued investment in oligopolies that are essentially importers, justice was not speeded up and bureaucracy was clearly not reduced.

The combination of these factors means that the Angolan economy has not yet emerged from the oil cycle and from repeating past mistakes.

The questioning of Agenda 2050

It is these basic deficiencies that appear to limit the effect of Agenda 2050. In a previous report we praised the unassuming and honest way in which the authors of the Agenda made the diagnosis of the past and present situation[6] , and we had some anticipation in reading the proposals for the future.

It is evident that Agenda 2050[7] has many interesting objectives and profound analyses that stimulate the debate, which should be broadened in Angolan society. However, at its core the document does not bring us the necessary ambition and has the defect of being based, as we have mentioned, on generalist models.

If we notice the essential core of the strategic objectives is hardly mobilising. The predicted increase until 2050 of the GDP is 2.4 times, which in terms of GDP per capita, assuming that the population growth is only 2.1 times (and may be much more) results in an increase from USD 3,675 to USD 4,215 of the mentioned GDP per capita. If we look at this, it is a rise in population welfare of only 14% in 27 years[8] . Add that unemployment will still be around 20%. An extremely high figure, although the statistical formula used by the National Statistics Institute of Angola (INEA) cannot be compared with others because it is more demanding and therefore presents more negative results .[9]

It is very discouraging. In fact, in view of the increase in population, what Agenda 2050 is putting as a goal is a quasi-progression. Is it not possible to do differently?

Angola in 2050 is supposed to be similar to what today are countries like Paraguay, Jordan, Sri Lanka, Essuatini or Mongolia[10] . We cannot subscribe to this vision, which in practice envisages a stagnant country where a sharper rise in population will pose severe problems.

Conclusions

In all independence and objectivity, we believe that this future Agenda should be fundamentally revised and substantially altered with the participation of the Economic and Social Council, the various study centres working on Angola in universities and elsewhere, and the country’s living forces, with a view to presenting a model that is both ambitious and feasible for Angola’s future. Only in this way will the current problems resulting from bad doctrinal models and little structural reformism be overcome.

Further and faster has to be the motto of the future.

[1] https://www.noticiasaominuto.com/economia/2347975/fitch-piora-perspetiva-de-evolucao-de-angola-para-estavel

[2] https://www.dw.com/pt-002/angola-queda-hist%C3%B3rica-do-kwanza/a-66037342

[3] https://www.jornaldenegocios.pt/economia/mundo/africa/angola/detalhe/angola-importou-mais-40-de-alimentos-no-valor-de-mais-de-dois-mil-milhoes-de-dolares-em-2022

[4] https://www.angonoticias.com/Artigos/item/74007/ministro-de-estado-esclarece-atrasos-salarias-no-pais

[5] https://www.cedesa.pt/2022/12/20/analise-da-proposta-de-orcamento-geral-do-estado-de-angola-para-2023/

[6] https://www.cedesa.pt/2023/06/11/estrategia-angola-2050-uma-analise-i/

[7] https://www.mep.gov.ao/angola-2050

[8] Idem, note 7, p. 22.

[9] https://www.makaangola.org/2023/05/desemprego-o-erro-das-politicas/

[10] Countries that currently have a GDP per capita close to 4125 USD. GDP, Per Capita GDP – US Dollars”, and 2018 to generate the table), United Nations Statistical Division.