Angola: The withdrawal of fuel subsidies and the transformation of political legitimacy

Rui Verde

- The decrease in oil revenues in the State Budget and the need for state funding

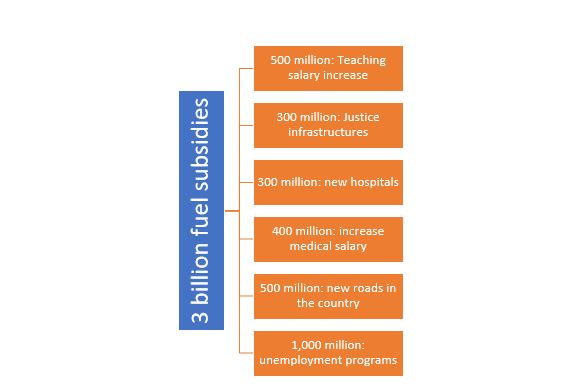

Following the guidelines of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Angolan government is gradually withdrawing fuel subsidies. The IMF defends this position because it believes that this measure will generate significant savings for the government and improve the state’s fiscal sustainability, since fuel subsidies represent a high cost for the General State Budget (OGE), reaching 9.1 billion kwanzas between 2021 and 2024. In addition, there are concerns about fuel leaks to neighboring countries and distortions in the domestic market . [1]

In a recent interview with LUSA, Angola’s finance minister, Vera Daves, confirmed that further cuts in fuel subsidies will be made this year, assuming that this is a “path that must continue”, although the speed depends on various factors .[2]

The truth is that Angola’s State Budget is facing ever greater challenges due to its historical dependence on oil revenues, a factor that jeopardizes the country’s financial stability . For decades, oil represented the main source of revenue, financing investments in infrastructure, health, education and other key sectors. However, the volatility of international oil prices has highlighted the need to diversify public revenues, especially since 2014.

For this reason, in recent years, the Angolan government has adopted tax and fiscal reform measures, seeking to strengthen non-oil revenue. The creation of specific taxes, the modernization of collection systems and incentives to formalize companies have reflected an attempt to reduce dependence on the energy sector. Despite these efforts, the budget deficit and the pressure on public accounts continue to be worrying challenges, as demonstrated by the delays that sometimes occur in paying the salaries of state workers, and the widespread delays in paying for supplies and services .[3]

The practical result is that the state needs to tax the population and cut spending that is irrational from an economic point of view[4] , as is the case with the fuel subsidy. This changes the pre-existing relationship between the state and the people. In the past, the state didn’t need the people to finance itself, now it does.

In fact, there are already around 5,205,380 individual taxpayers and 320,440 individual taxpayers with commercial activity in Angola, meaning that more than 5.5 million people are registered to pay taxes in the country[5] . While this is a remarkable number, it is also true that considering that there are around 14 million people with the potential to be taxpayers, there is still a lot of scope for broadening the tax base. At the same time, in 2022, Angola collected 4,638 billion kwanzas in non-oil taxes. Luanda province was responsible for 92.2% of this revenue. In the first quarter of 2023, non-oil revenue amounted to 976 billion kwanzas, an increase of 13% on the same period last year.[6][7] The key point is that non-oil revenue in Angola has shown significant growth in recent years . [8]

2-The need for taxes and subsidy cuts and the changing paradigm of political legitimacy

Since 2002, the political legitimacy of the Angolan system of government has rested on two factors: victory in the civil war and direct access to oil revenues.[9] In real terms, the people were not part of the equation for legitimizing power. José Eduardo dos Santos could govern without the people and without needing them. All he needed was military victory and oil money. The formal legitimizations of power, such as the 2008 elections or the 2010 Constitution, were just that, mere acts validating a previous reality that had been imposed.

Legally, the government was based on popular sovereignty and the Constitution, and all legal-formal acts were taken over time with a valid legal basis: elections, the Constitution, legislation, votes in parliament, etc. However, there was the notion that the constitutional and governmental system was based on a previous pact in which victory in the war and access to oil funds gave power to the government, which in return guaranteed the development of the country and the evolution of society. It is in this context that the political rationality of the fuel subsidy can be seen.

The point is that since 2014, when the price of oil fell enormously and Angola entered almost ten years of crisis, this political legitimacy has been destroyed. On the one hand, the generation and memories of the war have diminished. A large percentage of the Angolan population was born after the end of the civil war (2002). Around 65% of Angolans (more than two thirds) are under the age of 25, which means that 21 million Angolans are under this age group. This means that the legitimacy of the war already means little or nothing to them, as the victor has no right to exercise power.

In addition, the need to take revenue from the people and withdraw subsidies from them changes the 2002 social pact: if political power needs the people, then the people will participate in political power. There is no turning back from this equation that has been affirmed throughout history.

The payment of taxes has historically been a determining factor in the formation of political systems and the consolidation of democratic rights. In medieval England, the need to collect taxes led to the creation of institutions such as Parliament, where representatives of the nobility and the bourgeoisie discussed the king’s requests for money to pay for royal weddings or wars. The Magna Carta of 1215 was a milestone in establishing that taxation had to rely on some level of consent from the subjects, reinforcing the idea that government authority could not impose arbitrary taxes without representation. This principle evolved over the centuries, directly influencing the development of modern parliamentarianism .[10]

In the context of democracy, the concept of “no taxation without representation” became central. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England consolidated Parliament as a fundamental body in governance, restricting the absolute powers of the monarch and reinforcing the role of citizens in fiscal decision-making. The idea that taxes should be debated and legitimized by elected representatives helped shape democratic systems in Europe and North America. As nations sought greater popular participation, control over taxes became a crucial mechanism for defining citizens’ rights and strengthening representative democracy.

The relationship between taxation and independence became especially evident in the American Revolution (1775-1783). The British colonists in America rejected taxation without their direct participation in the decisions of the British Parliament. Legislation such as the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Tea Act of 1773 were seen as violations of colonial autonomy, leading to protests such as the Boston Tea Party. The refusal to accept taxation without representation resulted in the revolutionary movement that culminated in the independence of the United States, enshrining the idea that the legitimacy of a government depends on the participation of citizens in defining fiscal policies.

Thus, throughout history, the payment of taxes has not only been a means of financing states and governments, but also a catalyst for significant political transformations. Parliamentarianism, democracy and the independence of several countries were shaped by debates over who should have the power to define and collect taxes. The struggle for the right to influence tax policies contributed to the creation of institutions that ensured effective popular participation in government and the basis of its legitimacy.

3-Conclusion: the transformation of the political legitimacy paradigm in Angola

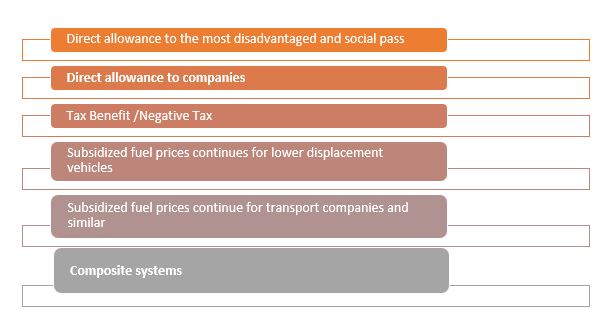

Political legitimacy in Angola is undergoing a significant transformation. The concept of the “right to govern”, previously associated with the MPLA, has lost its validity. This change reflects the growing awareness of the Angolan tax-paying population (and not recipients of fuel subsidies) of their role in sustaining the state, especially through the payment of taxes. The relationship between citizens’ tax contributions and the state’s ability to function has become a central element in the country’s political dynamics, transcending ideologies and public demonstrations.

This transformation marks a new phase in Angolan politics, where the power of the people is manifested in a more concrete way. The voice of citizens, based on their economic contribution, will redefine political arrangements and the structure of governance. This phenomenon highlights the importance of legitimacy that goes beyond mere legality, demanding a deeper connection between the rulers and the ruled.

The 2027 elections will represent a milestone in this context. For the first time, political legitimacy will be debated at the ballot box, transcending the legal sphere. This event promises to be a turning point in Angola’s political history, where the weight of social and economic transformation will have a direct impact on the choice of leaders and the definition of the country’s future.

[1] https://www.msn.com/pt-pt/pol%C3%ADtica/governo/governo-angolano-confirma-mais-cortes-nos-subs%C3%ADdios-aos-combust%C3%ADveis-este-ano/ar-AA1DGdmi

[2] https://www.angola24horas.com/sociedade/item/31715-governo-angolano-confirma-mais-cortes-nos-subsidios-aos-combustiveis

[3] https://observador.pt/2024/08/02/governo-angolano-diz-que-salarios-de-julho-dos-funcionarios-publicos-ja-foram-pagos/

[4] We have our doubts about this cut before the fuel market structure is reformed to make it a competitive market, but that’s a subject we won’t discuss here. See: https:

[5]https://www.ucm.minfin.gov.ao/cs/groups/public/documents/document/aw4x/mju4/~edisp/minfin1258130.pdf

[6] https://expansao.co.ao/angola/detalhe/luanda-arrecadou-922-do-total-da-receita-fiscal-nao-petrolifera-em-2022-60224.html

[7] https://forbesafricalusofona.com/impostos-arrecadados-pela-agt-em-angola-atingem-os-13-bilioes-kz-em-2022/

[8] https://www.opais.ao/economia/arrecadacao-nao-petrolifera-acima-dos-4-bilioes-de-kwanzas/

[9] Rui Verde, 2021, Angola at the Crossroads. Between Development and Kleptocracy, IB.Tauris. London.

[10] Rui Verde, 2000, The Harmonious Constitution. Judges and the Protection of Liberty. Newcastle upon Tyne.