Angola: The Employment Legislature

Electoral results and unemployment

The recent Angolan elections on August 24, 2022 were the subject of intense scrutiny by Angolan and international public opinion. Interestingly a good part of the attention was devoted to political and/or legal subjects. There was a great deal of courts, electoral processes, law application, voting counting, multitude of initiatives and even constitutional revision.

However, the qualitative inquiries that a partner executed during the election period did not point out these as the main concerns of Angolans, but those linked to the economy, namely employment and unemployment. What Angolans seem to ask above all is a job and good living conditions.

Consequently, the issue of unemployment is one of the most important in the activity of the executive who has now taken office.

At this time, the most current data point to a 30.2% general unemployment rate (data from the National Institute of Statistics for the II Quarter of 2022) and the youth unemployment rate (15-24 years) will be located in the 56.7%[1]. The unemployed population over 15 years old in the entire country is calculated in 4 913 481 of people, while young people from 15-24 unemployed is 3 109 296.

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estatística de Angola

Even if they doubt statistics and considering the very large weight of the informal economy, which makes calculations difficult, the reality is that the unemployment rate is too high. By the way, it is almost certain that the high rate of youth unemployment has manifestly contributed to the MPLA defeat in Luanda.

Unemployment is one of Angola’s most serious and important political, economic and social problems.

Government Employment Policy

Government policy regarding unemployment has been essentially passive, although accompanied by some concrete programs.

Essentially, the government expects the effort of macroeconomic stabilization (budgetary equilibrium, public account control, exchange rate liberalization, etc.) to translate into an incentive to private investment that in turn will increase employment.

The inaugural address of the President reaffirmed this approach when he said that “we will continue to work on policies and good practices to encourage and promote the private sector of the economy, to increase the offer of national production goods and services, increase exports and create more and more jobs for Angolans, especially for younger people”[2] (our emphasis).

The Minister of State for economic coordination, now reappointed, had already pointed out this direction when referring to unemployment and public employment promotion programs, he does not mention them concretely, but focuses on macroeconomic aspects. In early September, Nunes Júnior advanced that he was confident in reducing unemployment based on the private sector, claiming that the government was able to “put the country in economic growth giving currency stability and net international reserves” and placed “the country on the economic balance track, exchange rate stability and international reserves”[3].

The government successes in the area of stabilization of public finances and currency politics are not challenged, what is doubtful is the belief that the Angolan private sector has immediate ability to resolve the issue of unemployment.

On the basis of this non-interventional policy on the correction of excessive unemployment is the neoclassical model that summarizes the essence of all economic activity to the free interaction between supply and demand for price flexibility. The neoclassical model has a valid relevance in many areas of economic analysis, but certainly will not be applicable linearly in the job market[4] and even less in Angola.

The government continues to believe that it is sufficient to create the appropriate framework conditions (financial and currency framing) and employment emerges moved by the private sector.

This would be so if Angola were a free market economy with a strong and capitalized private sector. Angola is nothing like that. It is an economy that began with a process of destruction and Sovietization after independence in 1975 and whose “liberalization” after 1992-2002, it was false, or rather, was post-soviet, imitating Mother-Russian: some oligarchs linked to power took advantage of privatization and alleged free markets to quickly “hand in hand” with political power take dominant positions. In fact, there have never been true entrepreneurs, but essentially political entrepreneurs. And there was never a private sector, but a sector of friends of power. This reality has no strength to promote employment as the minister wants.

Making the recovery of employment in Angola dependent and combating unemployment only in the private sector is impossible.

There are two orders of reasons why the policy against unemployment is only based on the private sector.

Firstly, the operation of the market. As a general rule, the labor market does not function as a free market, by obeying the rules of supply and demand defined by the neoclassical economic model that seems to sustain government philosophy, the behavior of the labor market is tendentially rigid, wages are hardly lowered or people are fired without social turmoil and constraints.

In technical terms it is said that the labor market operates as a market without compensation (non-clearing market)[5]. While according to neoclassical theory, most markets quickly reach a balance without excess supply or demand, this is not true for the job market: there may be a persistent level of unemployment. Comparison of the labor market with other markets also reveals persistent compensatory differentials between similar workers.

Keynes in the context of the 1930s crisis studied the subject and concluded that the economy could go into underemployment balances, this means that it can reach a level where it will never employ all potential workers and not leave without the intervention of a “visible hand” that would be the State[6].

The second reason is the magnitude of unemployment in Angola. It is one thing to expect that the private sector hire people when unemployment is 10% and it is intended to go down to 6%.

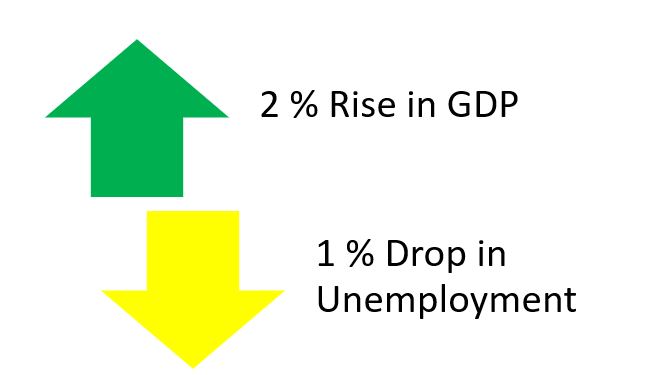

It is possible that economic growth automatically increases employment. Okun’s famous law[7], even though it is inaccurate, tells us that a 2% rise of the product (GDP) implies a decrease of 1% of unemployment. Thus, if Angola’s GDP increased 4% by 2023, unemployment would only drop 2%, i.e. to 28%. Manifestly insufficient.

Explanation of the Okun Law

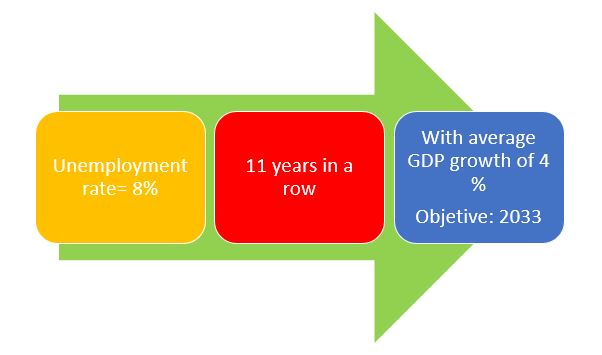

Therefore, there is a problem here for the economic theories in which the government rests on its policy. To go down unemployment to acceptable levels, for example 8%, 11 years would be needed with an average growth of 4% per year. Only in 2033 would unemployment be at a satisfactory level for the well-being of the population.

Exemplification of the necessary to achieve an unemployment rate of 8% without state intervention

Alternative and complementary policies

It is possible that this reality was what led the newly deposed minister of state to the social area, Dalva Ringote, to announce the “redinamization” of several government social programs. Although it has not specifically referred to unemployment, it is assumed that training programs, education programs and fighting poverty are included in the portfolio of the minister’s concerns and begins to have some inflection in the passive orthodoxy of the fight against unemployment[8].

It is evident that there are no miracles, but there has to be a government effort to idealize a more active employment policy than the private sector and expected economic growth supplemented.

Essentially this policy would be based on three pillars:

EMPLOYMENT PLAN

i) The hiring of staff for the State for the coverage of fundamental needs in education, health and social solidarity. Here the focus would be the hiring of licensed staff to occupy positions of human Capital that reproduce social welfare;

ii) The grant to private companies to hire contract workers, giving preference to Angolans;

iii) the launch of vast professional training programs for unlicensed citizens to provide them with practical qualifications in agriculture and in several posts.

In order to finance these massive programs to fight unemployment, one would have to rely, in part, on budget surplus funds and, on the other hand, on the famous recovery of assets in the fight against corruption.

There is no doubt that much of the government’s future is based on what will be done in the employment area. This will really have to be the employment legislature.

[1] INEAngola:https://www.ine.gov.ao/Arquivos/arquivosCarregados//Carregados/Publicacao_637961905091063045.pdf

[2] Presidência da República de Angola. Discurso de Investidura, 15-09-2022, in https://www.facebook.com/PresidedaRepublica

[3] https://correiokianda.info/governo-cria-programas-para-reducao-de-desemprego-no-pais/

[4] See a balanced description in Dagmar Brožová, Modern labour economics: the neoclassical paradigm with institutional content, Procedia Economics and Finance 30 (2015) 50 – 56.

[5] See for example: Willi Semmler & Gang Gong, (2009), Macroeconomics with Non-Clearing Labor Market, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.587.8716&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[6] The best explanation remains Paul Samuelson & William Nordhaus, Economics, 2019 (20 Ed).

[7] See previous footnote.

[8] https://www.verangola.net/va/pt/092022/Politica/32628/Dalva-Ringote-anuncia-%E2%80%9Credinamiza%C3%A7%C3%A3o%E2%80%9D-dos-programas-de-combate-%C3%A0-pobreza-e-seca.htm