Sonangol: the need for a new strategic vision

The Annual Accounts: 2019

On 22 September 2020, Sonangol presented its annual accounts with reference to 31 December 2019[1]. The net result was USD 125 million (one hundred and twenty-five million US dollars), equivalent to AOA 45 854 million (forty-five thousand, eight hundred and fifty-four million kwanzas), with EBITDA (Results before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization) of USD 4,779 million, representing an increase of 10% in relation to the previous year.

Revenues were identical to 2018, while operating costs fell 11%.

Oil production was also similar to the previous year while gas production increased by 6% and LNG by 8%. The production of refined products grew 37%, after resuming operations at the Luanda Refinery.

This is the accounts’ summary as announced by the Company’s Board of Directors[2].

Fig. 1 – Summary of Sonangol 2019 Accounts according to the Board of Directors

| ITEM | NET RESULTS |

| Net Profit | 125 M USD |

| EBITDA | 4,799M USD |

| Oil Revenue and Production | Similar 2018 |

| Gas | +6% |

| LNG | +8% |

| Refined Products | +37% |

The accounts make ample references to the ongoing Regeneration Plan, which has as essential goals to place the company’s focus on the activities of the oil industry value chain, that is: prospecting, research and production of crude oil and natural gas, refining, liquefaction natural gas, transportation, storage, distribution and marketing of derivative products[3].

Combating corruption at Sonangol and strengthening the role of Non-Executive Directors

The key issue of these accounts begins to be formal, as, finally, accounting reserves that lasted for 15 years were eliminated and the financial reporting is endowed with enhanced transparency.

An effort to eliminate Sonangol’s role as an “epicenter of corruption” is visible[4], that is, as the main public financier of the business and private pleasures of the Angolan ruling elite.

This can be seen in the attempt to improve the transparency of financial reporting and in the appointment of non-executive directors such as Marcolino Moco and Lopo do Nascimento, two individuals with recognized integrity. These are moves to ensure that Sonangol’s revenues are not used for these private businesses.

To these measures are added the termination of Sonangol’s functions as a National Concessionaire and the privatization of several expensive units of the group, which in many cases were only vehicles for withdrawing public money for private purposes.

However, within this framework it would be important that the Non-Executive Directors, in addition to publicly signing the report and accounts, issued a declaration of verification that there was no significant and visible appropriation of public funds by private entities. Transparency has to go further.

Fig. No. 2- Measures to combat corruption at Sonangol

Sonangol’s weaknesses:

If the first task of the Government and of the Sonangol’s governing bodies is to eliminate corruption[5] within the company, the second and no less important task is to make the company profitable and with prospects for the future.

And here despite the implementation of the so-called Regeneration Plan, this is not enough. A full qualitative leap is needed at Sonangol.

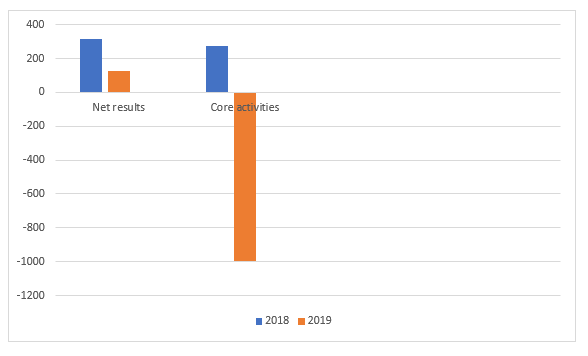

If we look at the company’s net profits, they dropped in 2019 to 46 billion kwanzas (about $ 125 million) compared to the 80 billion kwanzas ($ 316 million) in 2018. There are several reasons why this happened, from the low price of oil to the cessation of receiving supplies as a National Concessionaire. However, this number represents an additional weakness of the company.

In a study recently issued, Reuters[6] reported that Sonangol’s core activities in 2019 lost 351 billion kwanzas ($ 995 million), compared with a profit in 2018 of 69 billion kwanzas ($ 274 million) ). In 2019, debt payments were spent US $ 1.8 billion, while operating profits from oil production, sale and refining of US $ 1.570 million.

In addition, the total liabilities in 2019 were US $ 36 billion, referring to loans, risk provisions and accounts payable.

It should be noted, moreover, that the final net profit mentioned above is the result of unrepeatable extraordinary results such as cancellation of old debts and sales of some assets. They do not result from the central activity of the company.

KPGM points out that Sonangol’s liabilities or obligations exceed its assets, something that has not happened since 2016.

This means that the company’s core business is not competitive. Therefore, modeling the Regeneration Plan in a mere return to the core business isn’t the best solution.

This means that it is not enough for Sonangol to focus on its core business, as indicated by the Regeneration Plan. It is not enough and it cannot happen.

Fig. No. 3- Sonangol: Compared data between 2018 and 2019 (millions of dollars)

In addition, in 2019 Sonangol had sales of US $ 10 billion, 4% less than in 2018, which is understandable, as mentioned above, since in the middle of the year it stopped receiving earnings as a National Concessionaire. However, in addition to sales being stagnant, the production of barrels of oil is also stalled at 232 thousand barrels per day. In addition, it is feared that in the future oil will lose its importance in the world economy.

If we look at the amount of expenditure in the Angolan State Budget for 2020 in the revised version, it is US $ 23 billion. As only a part of Sonangol’s sales accrues to the State, we have a direct contribution from Sonangol to the national economy much lower than in the past. It should also be noted that the Angolan GDP is around US $ 105 billion. In this sense, Sonangol’s total sales do not reach 10% of GDP.

These elements lead us to two conclusions:

I) Sonangol’s oil activity is stagnant;

II) the company no longer has the magnitude to be the driving force of the Angolan economy.

These two conclusions have repercussions for the national economy and for Sonangol itself.

As far as the national economy is concerned, the solution is clear and is already beginning to be taken: broadening the national productive base, diversifying the sources of public income, promoting the creation of a strong agricultural and livestock support in the country, promoting the opening of companies, investment and competition in the market. It is a painful and difficult process, but a necessary one.

Harmonium Strategy. Going beyond the Regeneration Plan

Regarding Sonangol, it is understood that it is not enough and it is not the best idea to just focus on oil. The company’s reform has to be more ambitious and forward thinking.

On that matter we have already advocated in previous work[7] and it lays on the partial privatization of the company. The privatization of 100% of the company is not advocated, but the privatization of 33% of its capital in order to bring international investment, involvement of Angolan capital and motivation of its workers. These three objectives would be achieved through the following partial privatization model. Of the 33% of share capital to be privatized, 15% would be for foreign investors and would be the subject of an OFS (Public Offer for Sale) on an international reference exchange with abundant liquidity. The other 10% would be for national investors and would be subject to an OFS in Luanda. And finally, the remaining 8% would go to Sonangol workers, who would also become owners of the company for the ownership of their shares.

There would be new money, fresh ideas and people without connections to the past. This would allow a different approach to the problems and a renewed vision of the future.

However, in view of the negative evolution of the world and Angolan situation in recent months, partial privatization alone will not suffice, as the Regeneration Plan is not enough.

A new strategy for the company is vital.

The strategy no longer involves excessive attention to the oil focus. That which is not profitable and in which the company is not competitive must be sold. Free the company from its weaknesses. Decrease. But at the same time, increasing the company’s capacity and scale. Hence this option is designated as the Harmonium Strategy.

The remaining activities are expected to remain at Sonangol, while a renewal strategy is launched, based on developing a stronger downstream business, increased refining capacity, expansion for chemical products, and investing abundant renewable energy in Angola, such as sun and water, at the same time. time creating new technologies through its R&D efforts and developing new lines of business through investments and acquisitions. This means that there must be a transformational effort by Sonangol and not a mere reduction or dismantling.

It is necessary to follow what many large foreign oil companies, whether dominated by the state like Aramco (Saudi Arabia), or private like BP, are doing.

And this is turning the oil company into an integrated energy company driven by the production of resources focused on providing energy solutions to customers. Construction on a scale of investments in renewable energy and bioenergy, initial positions in hydrogen and creation of a global portfolio of gas customers; there are several options that Sonangol faces to become a modern and competitive company.

[1]https://www.sonangol.co.ao/Portugu%C3%AAs/ASonangolEP/Relat%C3%B3rio%20de%20Contas/Paginas/Relat%C3%B3rio-de-Contas.aspx

[2]https://www.sonangol.co.ao/Portugu%C3%AAs/Not%C3%ADcias/Paginas/Not%C3%ADciasHome.aspx?NewsID=472

[3]https://www.sonangol.co.ao/Portugu%C3%AAs/ASonangolEP/Estrat%C3%A9gias%20Corporativas/Paginas/Estrat%C3%A9gias-Corporativas.aspx

[4] See for example on the topic: https://www.makaangola.org/2020/09/sonangol-o-epicentro-da-pilhagem-de-sao-vicente-parte-1/

[5] We use the word corruption not in a technical sense, but in the current common sense in Angola, like all illicit private appropriation of public values, basically corresponding to what is criminally referred to as embezzlement, abuse of trust, economic participation in business, fraud, etc.

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/angola-oil-sonangol/angolan-energy-giant-made-no-money-from-oil-in-2019-as-debt-bites-idUSL8N2GP4V2

[7] https://www.cedesa.pt/2020/01/29/um-modelo-de-privatizacao-da-sonangol/