As consequências económicas em Angola da guerra da Ucrânia

É um facto que a guerra na Ucrânia está a afetar a totalidade da economia mundial, e, naturalmente, esse impacto também terá consequências políticas,[1] como aliás desde logo reconheceu o Fundo Monetário Internacional (FMI).

A questão que se vai abordar neste relatório é acerca do impacto específico da guerra na economia angolana, que como se sabe passa um tempo exigente de reforma e se apresta a sair duma crise profunda. Também se avaliará superficialmente se os impactos económicos terão influência política.

As duas faces do impacto do preço do petróleo em Angola

Naturalmente, que o primeiro impacto em Angola se refere ao preço do petróleo. A subida do preço do petróleo era uma tendência que já perdurava há algum tempo e foi acentuada com o deflagrar da guerra. Em certa medida, não é uma novidade trazida pela crise ucraniana, mas uma direção que já estava em curso há meses.

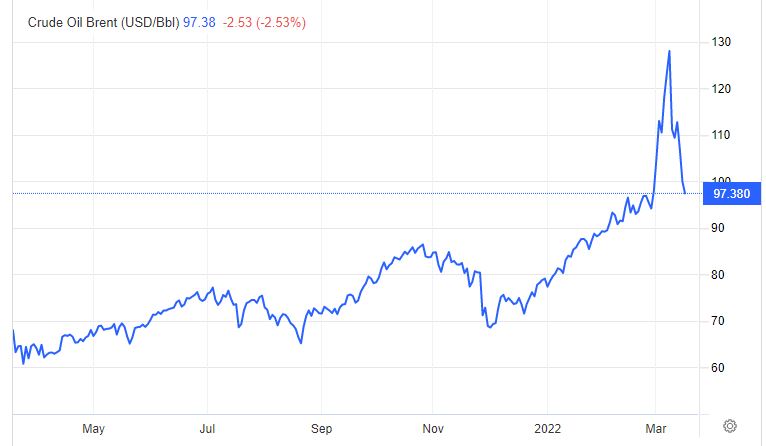

A 31 de janeiro de 2022, o preço do barril de Brent estava a USD 89,9, a 14 de fevereiro de 2022, o valor situava-se nos USD 99,2. É um facto que com o início da guerra chegou a atingir os USD 129,3 a 8 de março. Neste momento (16 de março), estabilizou nos USD 99,11. Parece que o preço de equilíbrio do petróleo nos próximos tempos andará entre os USD 95-100, havendo, obviamente, a possibilidade de choques que o façam subir ou descer abruptamente.

Fig. nº 1- Gráfico Diário do Preço do Barril de Brent (Maio 2021-Março 2022)

Fonte: Trading Economics.com

Em relação a Angola, temos de partir da previsão orçamentada para 2022 que calculou o preço do barril a USD 59. Portanto, haverá uma mais-valia desde o início do ano correspondente a mais 50%, no mínimo. Nesse sentido, como o orçamento estava equilibrado, quer dizer que haverá um excedente financeiro, o que obviamente é uma boa notícia.

Esta subida do preço do petróleo tem então, numa primeira linha, dois efeitos positivos para Angola.

O primeiro é ao nível da receita extraordinária do Tesouro que naturalmente aumentará. Em termos simples, pode-se afirmar que haverá mais dinheiro disponível por parte do Estado.

O segundo efeito, que também já se sente, é o chamado feel good factor (ou índice de confiança). Os empresários e as famílias refazem as suas expectativas num sentido mais positivo, esperando melhores sinais da economia. Segundo o Instituto Nacional de Estatística angolano, os empresários estão, finalmente, otimistas quanto às perspetivas da economia nacional no curto prazo, depois de permanecerem mais de 6 anos pessimistas.[2] A subida do preço do petróleo não é o único motivo para o otimismo revelado, mas ajuda.

Note-se, no entanto, que os ganhos do preço do petróleo não se transformam diretamente em saldo orçamental positivo. Há vários constrangimentos na tradução da subida do preço do petróleo em vantagens orçamentais diretas para Angola.

O primeiro deles é o tipo de relação com a China. A China é o principal comprador do petróleo angolano. Não sabemos de que forma estão feitos os contratos e se estes refletem automaticamente as oscilações de preço. No passado, alguns intermediários das compras e vendas de petróleo para a China chegaram a fazer contratos de preço fixo que prejudicaram enormemente o Tesouro angolano.[3] Imagina-se que tais “esquemas” já não existam, mas não há certezas. Certo é que, provavelmente, os contratos entre Angola e China referentes ao petróleo conterão algum tipo de “amortecedores” que implicarão que não haja uma repercussão direta dos preços. Além do mais, alguns peritos petrolíferos, como os da Chatham House, entendem que o facto de a China comprar cerca de 2/3 do petróleo angolano (na verdade 70%[4]) lhe permite um certo controlo monopolista do preço, querendo com isto significar que as compras chinesas são feitas de modo a minorar as subidas de preço, prejudicando as vantagens angolanas[5].

Em segundo lugar, temos o serviço da dívida. Aparentemente, existem mecanismos contratuais que implicam que um preço mais elevado do petróleo implica um aumento do serviço da dívida, isto é, dos pagamentos a efetuar. A ministra das Finanças, Vera Daves, já reconheceu que “o que resulta do aumento do preço não pode ser feita uma conta aritmética com a produção” e que o preço do barril de petróleo, acima dos cem dólares, obriga Angola a pagar mais aos seus credores internacionais[6].

Além do mais a subida do preço do petróleo tem também um possível efeito negativo no Orçamento angolano, que se refere ao preço dos combustíveis vendidos ao público. Como se sabe esse preço é subsidiado pelo Estado; nessa medida, se o custo do petróleo aumenta e o governo não aumentar os combustíveis, quer dizer que vai ter de suportar mais subsídios e gastar mais para manter os preços dos combustíveis. Se não o fizer pode estar a alimentar inflação, que já não é baixa em Angola e criar problemas sociais e de descontentamento.

Há aqui quatro fatores: aumento do preço, relações com a China, aumento das obrigações de pagamento de dívida e aumento do subsídio dos combustíveis que têm de ser tidos em conta para avaliar o real impacto da subida do preço do petróleo nas contas e economia angolana.

Na realidade, não dispomos de números precisos sobre esses impactos, apenas ideias de grandezas, e face a estas, a conclusão que se pode retirar é que um aumento de 50% do preço do petróleo em relação ao que está previsto no Orçamento deixa uma folga de tesouraria ainda acentuada depois do aumento do pagamento do serviço da dívida e do suporte à subida do preço dos combustíveis, sendo indubitável que uma “almofada” financeira será criada.

A esta “almofada” financeira, que, repete-se, não é diretamente proporcional ao aumento do preço do petróleo, acresce o fator feel good, de quantificação intangível, mas que já se nota nos principais atores económicos angolanos.

Quer isto dizer que depois de anos de grande sacrifício, há, finalmente, razões para um otimismo moderado relativamente à economia angolana.

A questão do preço dos alimentos

A par com o preço do petróleo, muitas outras classes de produtos básicos estão a aumentar de preço. Uma delas é a dos cereais, designadamente o trigo.

A Ucrânia e Rússia juntas respondem por um quarto de todas as exportações mundiais de trigo. O conflito está a elevar dramaticamente os preços do trigo. Com o início da guerra, o preço do alqueire de trigo subiu para US$ 12,94, 50% mais caro do que no início de 2022.

No meio de uma guerra, não está claro se os agricultores da Ucrânia estarão dispostos a gastar o capital que tiverem para plantar na próxima colheita, ou mesmo se estarão em condições de o fazer. O que é certo é que a Ucrânia anunciou a proibição de todas as exportações de trigo, aveia e outros alimentos básicos para evitar uma enorme emergência alimentar dentro de suas fronteiras. Portanto, exportações de trigo da Ucrânia, mesmo que exista produção, estão comprometidas.

Ao contrário do petróleo, que afeta os preços quase que no imediato, os preços dos grãos levam semanas, se não meses, para chegar aos consumidores. Na realidade, o grão cru precisa ser enviado para as instalações de processamento para fazer pão e outros alimentos básicos – e isso leva tempo. Nesse sentido, possivelmente, não será uma crise imediata para Angola, mas chegará ao país.

De acordo com fontes governamentais, Angola é autossuficiente em seis produtos agrícolas base: mandioca, batata-doce, banana, o ananás, os ovos e a carne de cabrito. No entanto, o trigo é a mercadoria mais importada, representando 11%.[7] Lembremo-nos que o trigo é um elemento essencial da dieta dos angolanos, o que aliás levou há alguns meses o ministro da Indústria e Comércio a sugerir a substituição do pão pela mandioca, batata-doce, banana assada e ginguba. Esta afirmação gerou muitas críticas. Contudo, do estrito ponto da autossuficiência económica talvez faça sentido, uma vez que possivelmente o preço do pão irá subir e eventualmente o preço dos bens nacionais pode descer, se existir mercado concorrencial adequado.

O que é certo é que Angola poderá correr o mesmo perigo do Egito, uma cultura extremamente assente no trigo que sofre perturbações sociais quando o preço do trigo sobe.

Quando os preços dos grãos dispararam em 2007-2008, os preços do pão no Egito subiram 37%. Com o desemprego a aumentar, mais pessoas ficaram dependentes de pão subsidiado– mas o governo não reagiu. A inflação anual dos alimentos no Egito continuou e atingiu 18,9% antes da queda do presidente Mubarak.

A maioria dos pobres nesses países não tem acesso a redes de segurança social. Imagens de pão tornaram-se centrais nos protestos egípcios que levaram à queda de Mubarak. Embora as revoluções árabes estivessem unidas sob o slogan “o povo quer derrubar o regime” e não “o povo quer mais pão”, a comida foi um catalisador. Aliás, note-se que os “motins do pão” vêm ocorrendo regularmente desde meados da década de 1980, geralmente após a implementação de políticas “aconselhadas” pelo Banco Mundial e pelo Fundo Monetário Internacional.

Angola não é o Egito, mas é fundamental que o governo esteja muito atento à evolução do preço do trigo e do pão para evitar agitação social, numa fase em que começa a sair da prolongada crise.

No entanto, tal como no caso do petróleo existe uma outra face, e neste caso é positiva. A crise da produção agrícola derivada da guerra pode ser um momento de inflexão para uma aposta em Angola de investidores estrangeiros na agropecuária. Angola é dos países do mundo com mais potencialidades, como aliás já referimos em relatório anterior[8], portanto este pode ser o tempo de oportunidades para investidores verem a capacidade agrícola angolana e desfrutarem dela. Um dos sectores mais promissores e com mais potencial é a agropecuária. Há neste momento uma conjugação de fatores que a tornam uma das apostas mais rentáveis para o investimento em Angola.

Conclusões e recomendações

A guerra na Ucrânia tem variados impactos na economia angolana.

A subida do preço do petróleo, não trazendo receitas diretamente proporcionais, cria uma “almofada” no Tesouro e um feel good factor no empresariado, que poderá ser potenciador de crescimento.

A subida do preço dos cereais, em especial do trigo, pode criar graves pressões inflacionistas e descontentamento entre a população, situação para a qual o governo deve estar atento. Ao mesmo tempo, chamará a atenção para o potencial enorme de investimento que Angola tem como país agropecuário.

O governo deveria criar uma reserva especial proveniente das mais-valias do petróleo para garantir o abastecimento de cereais à população mais carenciada e também para promover o investimento agropecuário em Angola.

[1] https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2022/03/05/pr2261-imf-staff-statement-on-the-economic-impact-of-war-in-ukraine

[2] https://www.angonoticias.com/Artigos/item/70611/optimismo-regressa-no-seio-dos-empresarios-seis-anos-depois

[3] Rui Verde, Angola at the Crossroads. Between Kleptocracy and Development (2021), p. 24.

[4] https://www.forumchinaplp.org.mo/pt/china-foi-o-destino-de-71-do-petroleo-exportado-por-angola-em-2020/

[5] Explicações dadas em reunião da Chatham House que aqui replicamos, respeitando as regras da casa.

[6] https://rna.ao/rna.ao/2022/03/03/preco-do-petroleo-a-cima-dos-cem-dolares-obriga-governo-angolano-a-pagar-mais-aos-credores/

[7] https://www.expansao.co.ao/economia/interior/grupo-carrinho-destaca-se-nas-importacoes-e-exportacoes-do-pais-106709.html

[8] https://www.cedesa.pt/2020/06/15/plano-agro-pecuario-de-angola-diversificar-para-o-novo-petroleo-de-angola/