Angola’s new strategic partners and Portugal’s position

Angola’s new strategic partners: Spain and Turkey

Two recent intense diplomatic exchanges at the highest level point to the emergence of new strategic partnerships for Angola. In a previous report, we warned of realignments in Angola’s foreign policy[1]. Now, what happens is that this realignment continues, and at an intense pace. The President of the Republic João Lourenço is clearly giving a new dynamic to Angola’s foreign affairs, which is not seen to be affected by some internal unrest on the way to the 2022 electoral process.

The most recent examples of the President’s diplomatic activity are Spain and Turkey. The important thing in relations with these countries, is not whether or not there is a visit at the highest level, it is about having an intensity of visits by both parties and clear objectives designed. It can be said that from a mutual perspective, Spain and Turkey are becoming Angola’s strategic partners.

Let’s start with Spain. Last April, the prime minister of Spain, Pedro Sanchez, who barely left the country during the Covid-19 pandemic, visited Angola. The visit was seen as marking a new era in bilateral cooperation between the two countries and led to the signing of four memoranda on Agriculture and Fisheries, Transport, Industry and Trade. The agreement regarding the development of agribusiness was particularly relevant, in order to build an industry that transforms raw material into finished product in the future, relying on the experience of Spanish businessmen. As is well known, agriculture is one of the Angolan government’s areas of investment in relaunching and diversifying the economy[2]. Therefore, this agreement is dedicated to a fundamental vector of Angolan economic policy.

More recently, at the end of September 2021, the President of the Republic of Angola visited Spain where he was received by the King and the Prime Minister. On that visit, João Lourenço clearly stated that he was in Spain in search of a “strategic partnership” that went beyond the merely economic and business sphere[3]. In turn, the Spanish authorities consider Angola as a “priority country”[4].

Now it will be seen how these broad intentions will materialize in practice, but what is certain is that both countries are clearly betting on an increase in both economic and political relations and their declarations and goals seem to have a direction and meaning.

The same kind of intensified relationship is being established with Turkey. Last July, João Lourenço visited Turkey, where he was extremely well received. From then on, it was agreed that Turkish Airlines would fly twice a week from Turkey to Luanda. It was also announced that Turkey has opened a credit line on its Exxim Bank to boost bilateral economic relationship. This means that the Turkish financial system will finance Turkish businessmen to invest in Angola. As early as October 2021, Turkish President Erdogan visited Angola. This visit was surrounded by all the pomp and circumstance and expressed an excellent relationship between the two countries. Like Spain, Turkey has an aggressive strategy for Africa, where it wants to gain space for its economy and political influence. The agreements signed by Erdogan and João Lourenço were seven, namely, an agreement on mutual assistance in customs matters; a cooperation agreement in the field of agriculture; an agreement for cooperation in the field of industry; a joint declaration for the establishment of the joint economic and trade commission; a memorandum of understanding in the field of tourism and a cooperation protocol between the National Radio of Angola and the Radio and Television Corporation of Turkey[5].

The approach with Turkey, like that of Spain, has as an immediate and structuring objective “that [the Turks] bring above all know-how that allows us to quickly and efficiently diversify and increase our internal production of goods and services”, using the words of João Lourenço[6].

In these two challenges by João Lourenço there is an obvious determination, or rather two.

First, seek new sources of investment that support the fundamental diversification of the Angolan economy. This is extremely important, and the Turkish and Spanish economies are properly diverse to be able to correspond to the model intended by Angola.

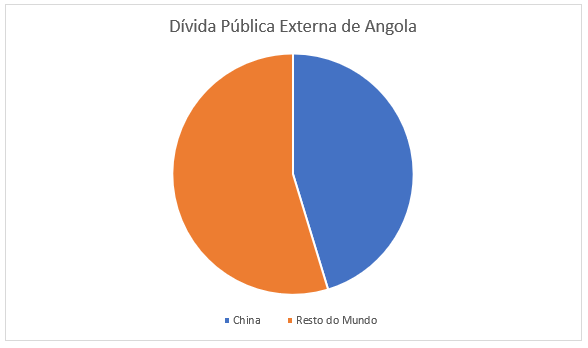

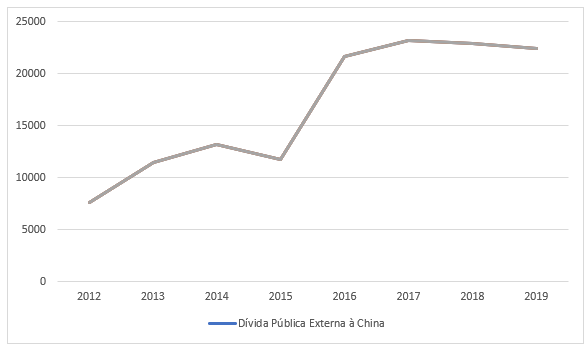

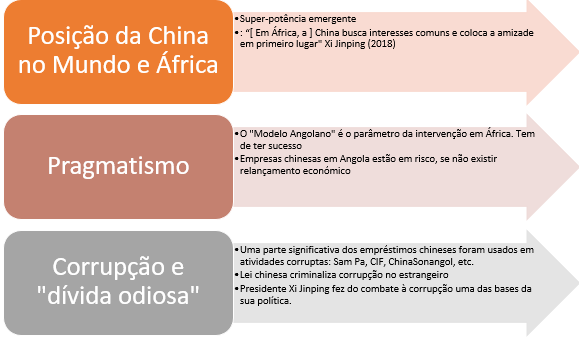

The second aspect refers to the need Lourenço feels to detach Angola from an excessive relationship with China and Russia, without harassing them, but looking for new partners. The geopolitical weight of the Cold War and the subsequent implementation of the Chinese model in Africa, with which Angola is identified, weigh heavily in the evaluations of foreign ministries and investors. Thus, Angola is looking for new openings and a “detachment” from that previous brand, not least because Russia does not have the financial muscle to make large investments in Angola, and China is in the middle of an economic turmoil. As we already know, “the Chinese economy grew 4.9% in the third quarter of this year, the lowest rate in a year, reflecting not only the problems it is facing with the indebtedness of the real estate sector, but also the effects of the energy crisis.”[7] This means that China needs a lot of Angolan oil, but it will not have financial resources for large investments in Angola.

In fact, the relations between China and Angola and the need for a reassessment of the same, especially in terms of oil supply and the opacity of the arrangements, will have to be a theme for an autonomous report that we will produce in the near future.

Portugal’s position. The ongoing deberlinization

Having established that the importance of the intensification of Angola’s relations with Spain and Turkey is established, an obvious question arises: and Portugal?

Portugal has tried to be Angola’s partner par excellence, and for this it has accommodated itself, in the past, to the several impulses of Angolan governance.

Currently, there are good political relations between Angola and Portugal. Just recently, João Lourenço said: “I was fortunate that during my first term in office we were able to maintain a very high level of friendship and cooperation between our two countries.” He also added that “personal relationships also help. Therefore, over the years, we have been able to build that same relationship with President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa and Prime Minister António Costa”.[8] There is no doubt that favorable relations are established between Angola and Portugal. It also helps that Portugal has three ties that are felt every day; historical ties, cultural ties, especially linguistic ties, and emotional ties.

However, despite the satisfaction expressed by the Angolan President regarding the good relations between the two countries, there are structural issues that cast shadows on the relationship and make Portugal’s position less relevant to Angola than in the past, generating some caution on the part of Angola in relation to excessive involvement with Portugal. Actually, there is a decline in the Portuguese position in Angola, vis-à-vis Spain or Turkey, or Germany, France or the United Kingdom. There is an ongoing de-Berlinization of Angola’s foreign policy. João Lourenço sees Portugal as an ally in the CPLP, but not as a gateway or platform to Europe. There, he wants to relate directly to each of the specific European countries. The old idea that pervaded in some European chancelleries that Angolan topics were specific to Portugal and should be dealt with from, or at least, with the Lisbon competition (which we call Berlinization), ended. Each of the European countries now deals with Angola without Portuguese intermediation and vice versa.

This fact results essentially from three factors. One of an economic nature, and two of a political nature.

In the first place, Angola seeks, in its foray around the world, countries with the potential and capital to invest. It is searching for capital to develop its economy. Now Portugal, jumping from crisis to crisis and having a clear lack of capital for its development, will have much less means to move to Angola. And in the famous Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Plan there is nothing specific for investment in Africa or Angola in particular. Consequently, with no provisions highlighted for Angola in the Portuguese Plan, it is clear that the African country will have to go looking for massive investments elsewhere.

However, we believe that this is not the main cause for the relative decline of the Portuguese position in Angolan foreign policy priorities. There are two other reasons, which are interlinked.

In this sense, there is na element that has caused the disquiet of the current Angolan leadership towards Portugal. This element entails in the fact that in the near past, Portugal constituted what the Financial Times of October 19th[9] described as the place where Angola’s rich (and corrupt) elite collected trophies in assets, a kind of playground for the President’s sons José Eduardo dos Santos and other members of the oligarchy. Now, the Angolan government, apparently, looks with some suspicion at Portugal because of this, specially considering the intervention that banks, lawyers, consultants and a whole myriad of Portuguese service providers had in the laundering and concealment of assets acquired with illicitly withdrawn money of Angola. There is a danger that all these entities are making efforts to undermine the famous fight against corruption launched by João Lourenço.

What happened during the years of inspiring growth in Angola, between 2004 and 2014, significantly, is that Portugal acted as a magnet for Angolans’ savings and income. The Angolan ruling elites, instead of investing the money in their country, went to invest it, or merely park it in Portugal, with disastrous consequences for Angola, which found itself without the necessary capital to make its growth sustainable. The reasoning that can be attributed to the Angolan government is that Portugal allowed the Angolan money obtained illicitly to be laundered in its economic and financial system with such depth that it is now very difficult to recover. Ana Gomes, wisely, always warned about this. In fact, if we look at the assets recovered by Angola, with great significance, there has not yet been public news that any of them came from Portugal. There was the 500 million dollars that came from England, but in Portugal, EFACEC was nationalized by the Portuguese government – and that’s okay from the Lisbon’s national interest point of view- but it was realized that Angola would not receive anything from there, as well as one can’t regard a clear path of receiving from other situations.

To this phenomenon is added a second that is presently noted. Lisbon is serving as a platform for the more or less concealed articulation of strong opposition attacks on the Angolan government. Whether through consultants, press or law firms. In this case, unlike possibly in the case of investments and possible money laundering, these activities will take place in accordance with the law and adequate protections of fundamental rights. However, it will create discomfort in the Angolan leadership, which will possibly see a link between the two phenomena, that is, between the fact that Portugal was a safe heaven for Angolan assets obtained illicitly in the past, and now it has become a local of opposition and conspiracy, above all, to the so-called fight against corruption. It is noticed that many of the movements take place in Portugal and its elites continue to help those who were dubbed by João Lourenço as “hornets”, either judicially or in the search for new places to hide their money.

In concrete terms, the episode of EFACEC nationalization combined with the recent judicial decision to “unfreeze” the accounts of Tchizé dos Santos in Portugal, and the generalization of an anti João Lourenço current in large spaces of the Portuguese media, although they constitute decisions or attitudes that are justified in political, legal or ethical terms in Portugal, they are events that reinforce some Angolan distrust of the Portuguese attitude, which can see the former colonial power in a kind of shadow play.

These situations, which have broadened in recent months, are causing some discomfort in Angola, which may consider Portugal as a kind of safe haven for activities that harm the country. Gradually, conspiracies from Portuguese territory abound, such as meetings and other events

It is precisely the reasons mentioned above that lead us to identify some attempt at political distance between the Angolan government and Portugal. There are no easy answers to these equations, although its enunciation has to be made for reflection by all those involved.

[1] CEDESA, 2021, https://www.cedesa.pt/2021/05/18/os-realinhamentos-da-politica-externa-de-angola/

[2] See report CEDESA, 2020, https://www.cedesa.pt/2020/06/15/plano-agro-pecuario-de-angola-diversificar-para-o-novo-petroleo-de-angola/

[3] Deutsche Welle, 2021, https://www.dw.com/pt-002/jo%C3%A3o-louren%C3%A7o-em-espanha-em-busca-de-parceria-estrat%C3%A9gica/a-59344760

[4] Idem note 3.

[5] Presidência da República de Angola, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/PresidedaRepublica

[6] Idem, note 5.

[7] Helena Garrido, 2021, https://observador.pt/opiniao/o-choque-energetico-e-o-orcamento-em-duodecimos/

[8] Observador, 2021, https://observador.pt/2021/10/22/pr-de-angola-ve-relacoes-de-amizade-e-cooperacao-com-portugal-em-nivel-bastante-alto/

[9] Financial Times, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/4652e15a-f7ba-4d21-9788-41db251c5a76