Angolan Economy trends, necessary reforms and national employment plan

Social life in Angola is very alive and, at this moment, political and judicial matters dominate the country’s agenda. However, it is in the domain of the economy that there is an extremely significant evolution on which it is important to reflect and proceed to a careful analysis.

The recent (February 2023)[1] International Monetary Fund (IMF) report on the country underlines the favorable advances of the Angolan economy and also the necessary reforms. It is based on this report that we will enunciate Angola’s main trends in the economic field and the neuralgic points to avoid relapses such as the last long recession that began in the presidency of José Eduardo dos Santos.

Positive Trends

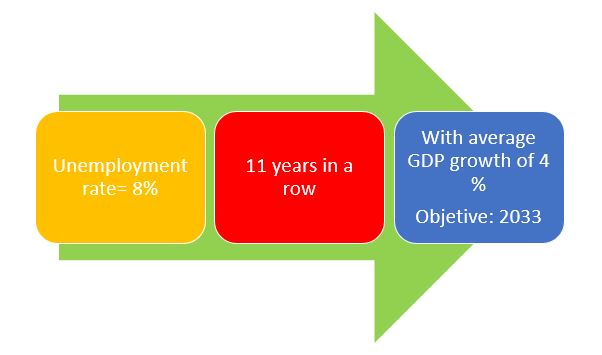

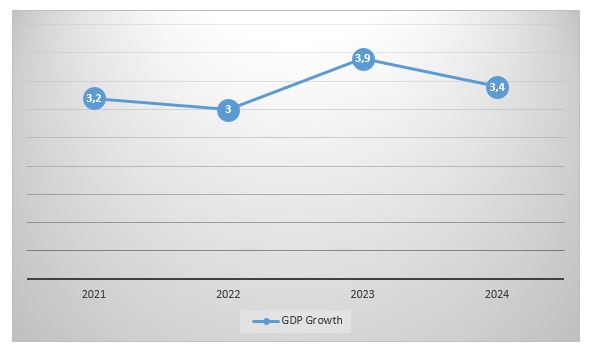

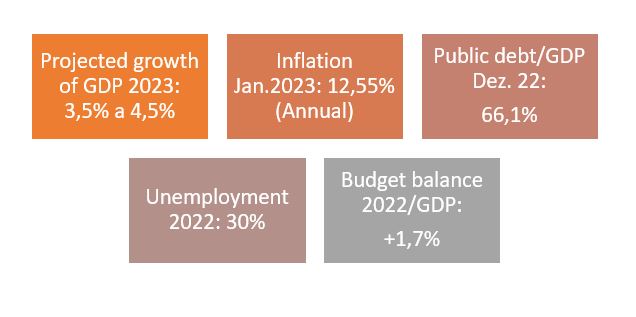

Angola’s economy is in full recovery after the five-year recession (2016-2020). By 2022, supported by higher oil prices and resilient non-oil activity, it has already reached growth of more than 3%, estimating the IMF that by 2023 the country continues to see the GDP increase in the order of 3.5%.

Therefore, we see growths of over 3% per year, which by our calculations, maintaining the price of oil and accelerating the liberalization of Angolan markets and foreign investment, could accelerate to numbers of 4% or 5%, adopted that are the right policies.

The optimism we share here results from the fact that non-oil growth has been widespread, despite a difficult external environment, as it means that the non-oil sector is reviving, as well as the attention that several developed countries with market economies are providing Angola, as is the case of US, Spain, France and Germany. Mentions should be made to recent visits to Angola of the King of Spain and the President of the French Republic, Emmanuel Macron (February and March 2023).

It should be noted that the debt that the public debt/GDP ratio has dropped about 17.5 percentage points of GDP, for an estimated 66.1% of GDP, aided by a stronger exchange rate. It is estimated that the checking account remained with a large surplus in 2022, while coverage of foreign currency reserves remained adequate (IMF data).

The fact is that the Angolan government has, according to the IMF, to adopt and maintain solid macroeconomic policies and maintained a commitment to structural reforms that are vital to Angola’s economy.

Necessary reforms

We understand that it is in the verification of fundamental structural reforms that resides the future of the Angolan economy. We highlight some reforms that are necessary to take and/or continue.

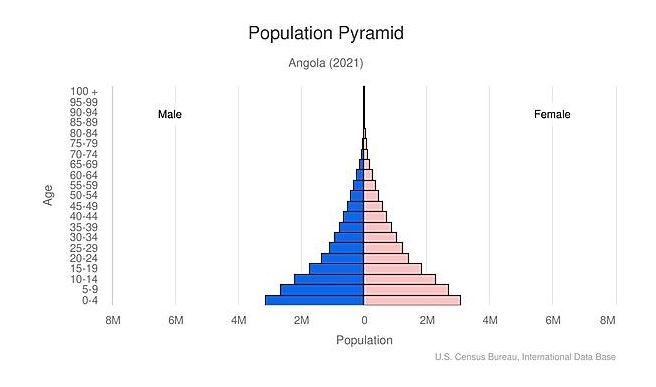

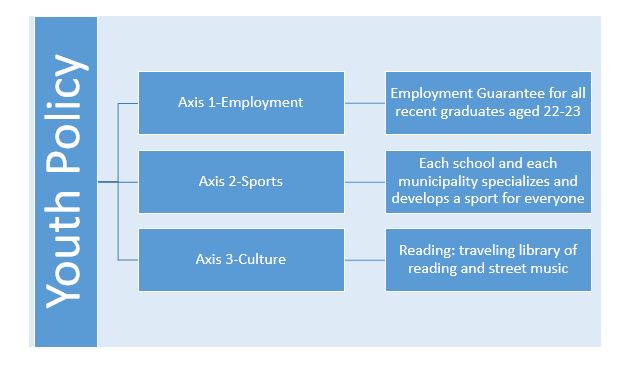

1-First renovation, with impact on the medium and long term, is to foster training for the economy of young people. Training not only means, and perhaps not in most, university education, but solid training in basic education and in professional aspects. We argue, therefore, that there must be an effective bet on vocational and technical education in Angola, before any other. A real bet on professional and technical schools and institutes, which are seen as valuable alternatives to academism and not mere university imitations (tragic error of Portuguese polytechnics).

2-Second renovation entails the creation of more conditions for investment, no longer at the legal level, where there is a modern framing and updated twice during the presidency of João Lourenço, but at the judicial, administrative and good practices level. The investor must feel safe to arrive in Angola and apply his money. One should not be afraid of being without the money due to any interference from an oligarch, or see any process dragging on in court. The speed and impartiality of justice is linked to good investment.

3-Third reform is dedicated to the financial sector, there is a special emphasis on increase credit to private persons and and the resolution of banking weaknesses. Quickly we must merge and capitalize banks, creating a banking sector not dependent on the state, clientelism or mere public debt management.

Finally, among other reforms, we highlight the true imperative of making more progress in strengthening governance and transparency, to improve the business environment and promote private investment.

Of course, continuing and accelerating anti-corruption strategy is also important.

National Employment Plan

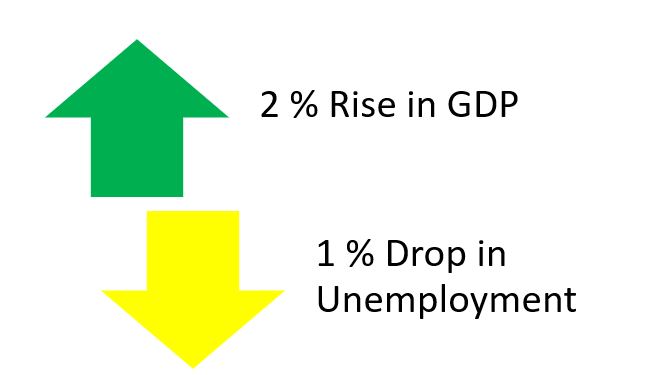

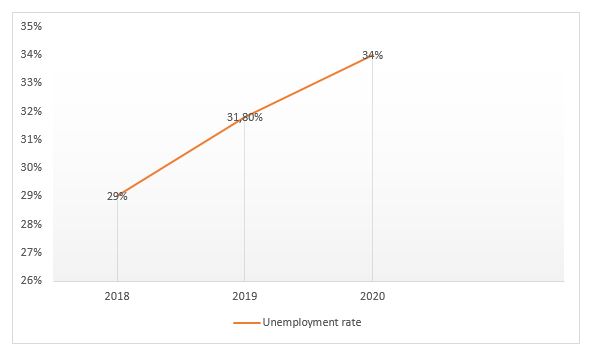

All these news should be framed with the well-being of the population and the serious problems still pending. The one we highlight is unemployment, which although noting a slight descent, is still very high, about 30% [2]. This is an area in which we advocate direct state intervention. It is evident that the increase in GDP corresponds to an unemployment decrease, however, we believe that in the face of such high unemployment, in the short term the immediate action of the government is fundamental.

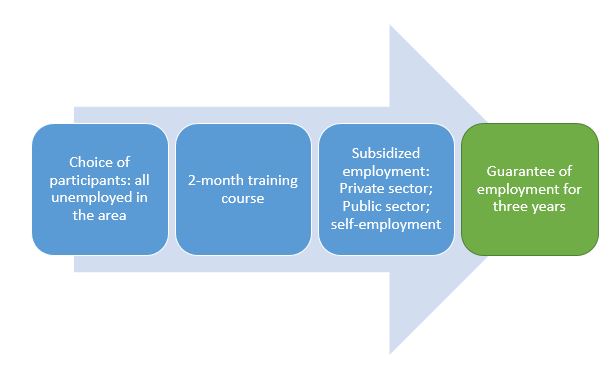

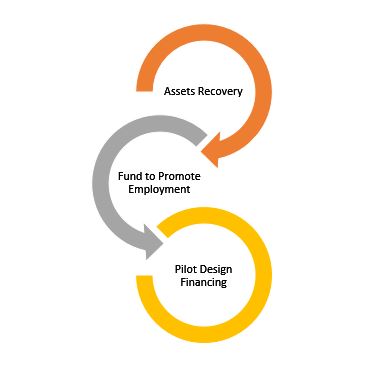

In this sense, the recent announcement of the World Bank of US $ 300 million for a project to accelerate economic diversification and job creation[3] is to greet. Not knowing in detail the design of this acceleration program, its existence should be underlined, as well as the previous announcement of the Angolan Labor Minister of the creation of a National Employment Program, with the aim of creating more opportunities for insertion of young people in job market[4]. Also, in this case, the data are scarce about the design of the plan, and it is certain that the President of the Republic had declared in the discourse of the State of the Nation of 2022, the creation of the referred plan.

So far, these initiatives related to unemployment, although positive, seem uncoordinated and poorly implemented. Therefore, the truth is that Angola would win to see a comprehensive national employment plan, specific and directly coordinated by the President of the Republic, without the risk of not properly implemented a plan, which in the short term is fundamental to the economy and Angolan population.

Fig.N. º1- Key Numbers of the Angolan Economy

[1] https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/02/23/pr2352-angola-imf-executive-board-concludes-2022-article-iv-consultation-with-angola

[3] https://correiokianda.info/banco-mundial-financia-usd-300-milhoes-para-fomento-do-emprego-em-angola/

[4] https://www.jornaldeangola.ao/ao/noticias/programa-nacional-de-emprego-e-implementado-este-ano/