Sonangol & Galp: what future together?

0-Introduction. Failure to take advantage of synergies between Sonangol and Galp

It was a recent article in the Jornal de Negócios, by its director Celso Filipe, which drew attention to the lack of synergies between Sonangol and Galp[1] and which serves as a starting point for this note on the topic.

Sonangol is the Angolan oil company and for many years it has been the real core of the country’s economy. In fact, it still is, despite the government’s diversification policy. In technical terms, the group consists of Sonangol E.P. (a public company) and a myriad of subsidiaries[2]. Galp is a Portuguese group also linked to oil, which includes several companies such as Petrogal, Galp Energia etc[3]. Obviously, Sonangol is the giant of the Angolan economy, while Galp is one of the largest companies in Portugal, alongside EDP.

The interesting thing is that since 2005, Sonangol has been a shareholder of Galp, although such participation is not assumed directly, but through a company of the Amorim family. It is known that, in an initial phase, this participation was publicly attributed to Sonangol, but then the daughter of President José Eduardo dos Santos, Isabel dos Santos, emerged as the holder of interests in the same participation, and there was sometimes factual confusion between what belonged to Isabel dos Santos and Sonangol. Today there is a dispute between the position of Sonangol and that of Isabel dos Santos, which led to the investigation of the latter in the Netherlands, where the vehicle company that it uses to control its position is headquartered[4].

Therefore, we have more than 15 years of indirect participation by Sonangol in Galp. The curious thing is that during that time, Sonangol and Galp never really sought to create synergies between the two companies. Sonangol’s participation was limited to being seen as a financial participation. Sonangol invested money and received dividends from that money. Nothing else. As Celso Filipe points out, in the aforementioned article: “Sonangol never sought to create industrial synergies with Galp, which could benefit the activity downstream and upstream of production and even improve its profitability.”

• The approach of Sonangol’s partial privatization requires that its holdings be valued to the maximum and the exploitation of synergies is done in the most efficient way so that the company obtains the best price for the sale of part of its shares.

• In addition, the current Angolan economic crisis requires an additional effort by its largest company to increase profitability.

These two reasons make it imperative to revisit the topic of Sonangol’s participation in Galp in order to see what is the best way to maximize its usefulness.

With this objective in mind, we will start by defining Sonangol’s current position at Galp, and understand its formal justification, suggesting a change, then we will try to find explanations for the purely financial strategic position that the Angolan company adopted in its Portuguese counterpart and finally, we will explore the various options for the future.

1- Sonangol’s position at Galp

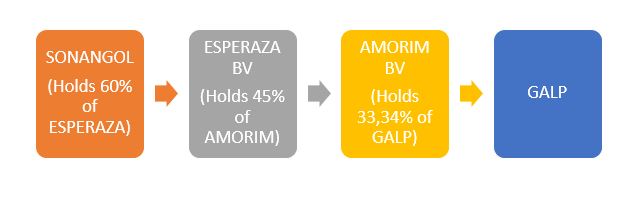

What results from Galp’s public corporate documents is that Sonangol does not hold any direct stake in the Portuguese oil company. Galp’s largest shareholder is Amorim Energia, BV with 33.34% of the capital, followed by Parpublica (which holds the Portuguese State’s shareholdings) with 7.48% of the capital and several investment management companies such as Massachusetts Financial Services Company, T. Rowe Price Group, Inc. and BlackRock, Inc. with about 5% each. Then there is Banco New York Mellon and Canada’s Black Creek Investment Management with around 2%[5]. This list of reference shareholders includes a company based in the Netherlands with the name Amorim, the Portuguese State and several American financial institutions. Sonangol does not appear.

In fact, Sonangol’s position is associated with the Dutch company Amorim. Sonangol holds the majority of the capital of a company called Esperaza Holding BV (also based in the Netherlands). In turn, Esperaza participates with 45% of Amorim.

This means that Sonangol has a minority position in Galp’s majority company. If Sonangol represents 45% of Amorim’s capital, it is clear that the Amorim family owns the other 55%. In turn, it seems that even in Esperaza Sonangol’s position is not total, since it shares it with Isabel dos Santos, with a dispute between them that it will not be cured here, since it does not affect the assumption that Sonangol controls Esperaza.

Fig. No. 1- Sonangol’s indirect participation in Galp

In a way, Sonangol’s position appears “sandwiched” between the Amorim and Isabel dos Santos, effectively lacking strategic room for maneuver and not having a decisive role at Galp, since it is always mediated by the Amorim.

Is the doubt that persists one see the reason why Sonangol accepted to participate in Galp in a dependent and submissive position to the Amorim? Was it a political demand from the Socrates government at the time, to avoid an overpowering onslaught by Angola? Was there shyness or ineptitude in negotiations on the part of Angola? Or was it a strategic formulation of Isabel dos Santos to appear unseen? We have no elements to justify this indirect choice.

• What can be said today is that Sonangol’s indirect position is detrimental to the appreciation of its shares as it is always dependent on a third party, in this case the Amorim, and does not have direct access to the company. This does not give value to the position or give it room for strategic maneuver.

What can be seen is that Sonangol’s stance enhances the Amorim’s leading role as they, with a mere 18.33% of the company, control 33,34%. We do not know whether Sonangol receives (or has received) any “prize” from the Amorim for this contribution or if there is any shareholder pact.

If there is no “prize” or shareholder agreement that benefits Sonangol, the truth is that, from Sonangol’s point of view, what will make the most sense is to split its position from Amorim and make its participation in Galp independent. This, as mentioned above, will give financial value to the participation as it becomes direct, and will give the Angolan company more strategic room for maneuver. This element is even more relevant at a time when it seems that strategic differences between the Amorim and the Galp’s CEO, Carlos Gomes da Silva, led to his hasty departure from the helm of the company. We don’t acknowledge the role Sonangol played in this divergence and its resolution, if any.

2- Possible reasons for the “passivity” of Sonangol’s position in Galp

As we have been saying, Sonangol’s role in Galp has been passive, essentially limiting itself to receiving dividends and not looking for any strategic synergy. The question that arises is why such a large and important participation, which several Sonangol CEOs consider in their public speeches as strategic, ended up being nothing more than a financial investment?

The first reason to justify such behavior is of a formal nature. Since Sonangol is not a direct Galp shareholder, it did not have the necessary means of influence to propose and create any synergy. This justification seems to us too formalistic and does not necessarily correspond to reality. However, it should be noted that in 2020, regarding several controversies involving Isabel dos Santos, Galp’s CEO, Carlos Gomes da Silva, was not afraid to affirm that “Isabel dos Santos is not a direct or reference shareholder [ of Galp] ”, adding“ The long-term reference shareholder is Amorim Energia, which is controlled by the Amorim family [6]”. Although the context of these statements is perceived, they still represent an effective disregard for the Angolan position, but that basically corresponds to the truth.

A second reason for Sonangol’s passivity is linked to the preponderant role that Isabel dos Santos played in Galp’s Angolan participation. The businesswoman only worked for a short time in Sonangol (2016-2017), in the remaining time, that is, between 2005 and at least until the emergence of several controversies in 2019/2020, her position was that of a private entrepreneur. in constant investment process. Isabel dos Santos did not stop in the extension of her “economic empire”, making purchase after purchase, investment after investment. In Angola, in addition to the initial investment in Unitel (a leading telecommunications company), Isabel dos Santos, as of 2008, enters several sectors such as distribution, banking, and hospitality. In banking, in addition to participation in BFA, the foundation of Banco BIC, in the distribution sector, launched Candando. In Portugal, she participated in BPI, bought BPN, took a stake in what is today NOS, in addition to Galp. She also bought vast real estate.

There is a pattern in Isabel dos Santos’ business activity, that of the investment cascade, using loans or dividends from one company to acquire others, not worrying, at this stage, in strategically integrating her business conglomerate. Now, the behavior observed in the construction of Isabel dos Santos’ “empire” and the possible political control that she assumed for some years over the Angolan participation in Galp, may have implied an option for receiving dividends as a priority. In fact, Isabel dos Santos would need Galp’s dividends to cover her expenses and, without having other relevant oil interests, there would be no focus on building synergies.

This is a working hypothesis that, of course, needs to be confirmed as the documentation on the involvement of Isabel dos Santos in the control of the Angolan position at Galp, between 2006 and 2016, is made public.

• However, what appears to be that the determining interest in this Angolan participation in Galp in the referred period was that of Isabel dos Santos and her main concern was to obtain funds for investment in its expansion and maintenance of its business conglomerate.

Obviously, this hypothesis does not explain the apathy observed after Isabel dos Santos left. Since 2018, there have been no special moves by Sonangol vis-à-vis Galp. At this stage, this inertia can be justified by the strategic uncertainty that has plagued Sonangol and also its participation in Galp.

In one way or another, this is the imperative time to take a rational stand on this participation.

3- Sonangol’s several options vis-à-vis Galp

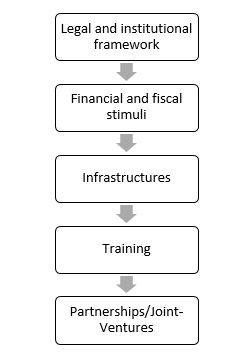

When the Angolan oil company is in the process of restructuring and intends to privatize part of the capital, it is essential to consider what it will do in relation to its participation in Galp.

There are several hypotheses for action. To better analyze them and discover the most appropriate course, it is pertinent to approach the strategies that each of the companies is following, since both are in a moment of reconfiguration.

Sonangol’s strategy

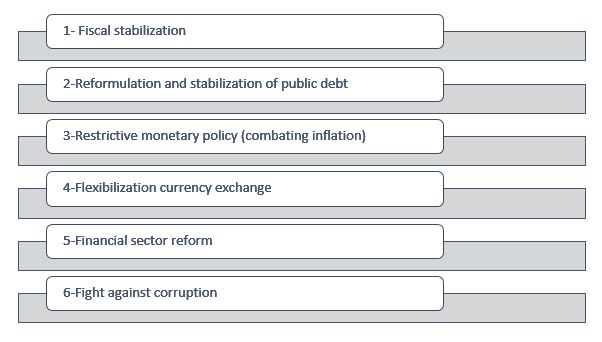

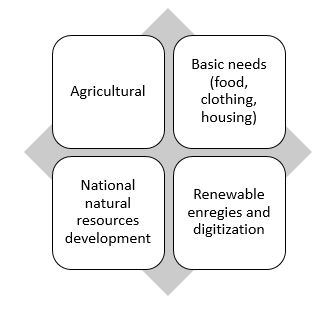

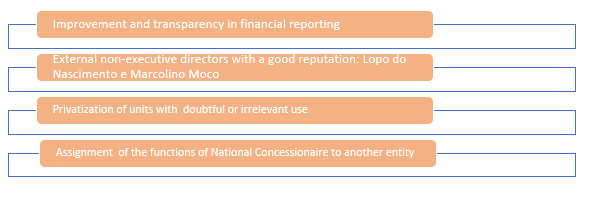

As for Sonangol, the strategy followed is based on several vectors, of which we highlight[7]:

-Like several of its counterparts, ARAMCO or BP, the oil company wants to become greener. It is also intended to permanently move away from the image of corruption. The plan for the next seven years, focuses on renewable energies and the relaunch of exploration and production in several oil blocks. In particular, Sonangol intends to:

– Increase the capacity of operated production of crude oil, with a target of not less than 10% of national production, instead of the current 2%.

– Invest in several oil blocks in order to increase net rights, with the relaunch of exploration and production in several oil blocks expected this year (blocks 3/05, 3 / 05A, block 5/06, Kon 4, as well as the cooperation, together with Total, of blocks 20 and 21, three years after the first oil).

– Optimize and modernize the Luanda refinery and ensure an increase in refining capacity, with investment in new refineries, in order to reverse the fuel import situation.

– Increase the capacity to distribute LPG [liquefied petroleum gas], monetize LNG [liquefied natural gas] and invest in renewable energy projects.

– Consolidate the company’s position as a reference player in the shipping segment in the region.

– Reinforce the position of trading crude oil and refined products in the international market, thus leveraging additional sources of revenue collection in foreign currencies.

– Increase onshore storage capacity, replacing floating storage.

-Optimize the retail network, aiming to consolidate the position of largest distributor of liquid hydrocarbons in the national market, in an environment that is increasingly liberalized, as well as relaunching the distribution and commercialization activity in other countries in the region, of which we have already the re-entry process is underway in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

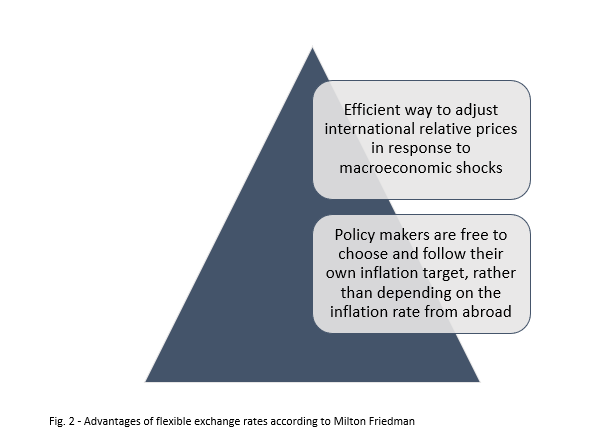

Galp’s strategy

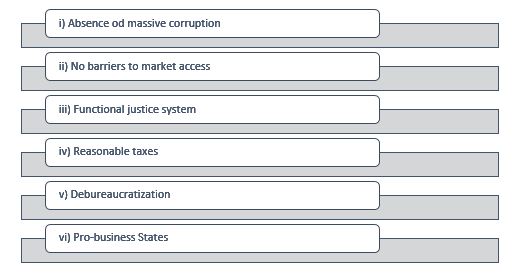

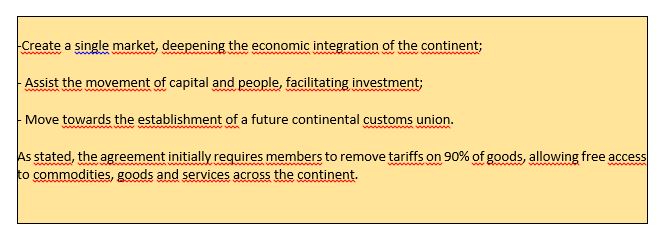

Galp is also in a strategic transition phase[8]. Decarbonisation has now become a priority, already manifested in the decision to close the Matosinhos refinery and the Sines Thermoelectric Power Plant. In fact Joana Petiz at Dinheiro Vivo[9], says that it was the Amorim’s commitment to accelerating the energy transition that led to the shortening of Carlos Gomes da Silva’s mandate and the appointment of Andrew Brown. Brown will have a mandate to bring about an intense change in Galp’s business, which is already advanced in its energy transition. In reality, Galp is the largest producer of solar energy in the Iberian Peninsula and invests in lithium, having acquired 10% in the company to which the lithium exploration in Portugal, Savannah Resources, was handed over.

However, despite these movements, oil is the company’s main source of revenue, with a special emphasis on holdings in Brazil, which make a substantial contribution to the company’s sustainability. Apparently, this will be where the financing for new projects “like gas in Mozambique – an intermediate step in the transition to cleaner energy – will come from, as well as the new bets from the oil company, including the exploration of lithium in Portugal[10]”.

Brief comparison between Sonangol and Galp

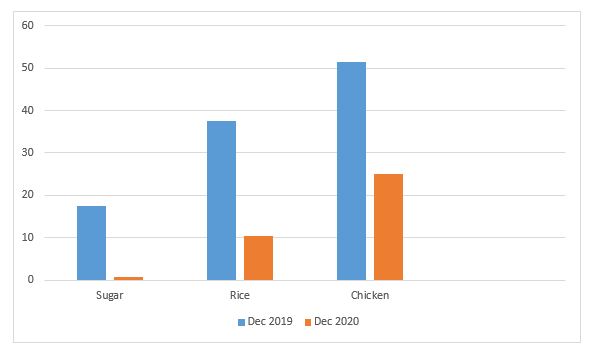

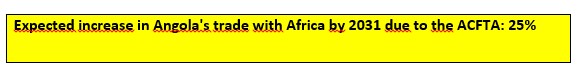

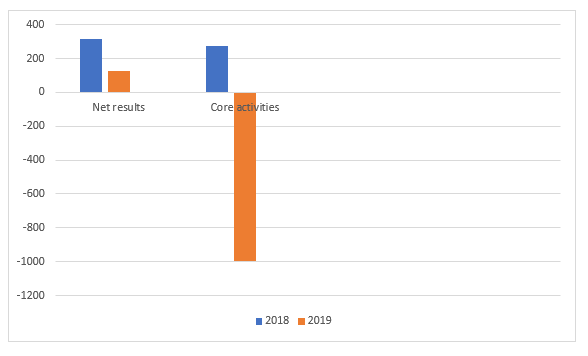

In 2019, according to the Reports and Accounts, Sonangol obtained total revenues in the order of US $ 10 billion, and an EBITDA of 5 billion. In turn, Galp achieved revenues of more than 19 billion dollars and an EBITDA of just over 2.5 billion dollars. Both companies affirm they are committed to an energy transition, this bet being more visible in Galp, but in terms of revenues both are dependent on oil.

Fig.2- Galp / Sonangol comparative table (source Annual Reports 2019, quot. € / $ to 5-2-2012)

| Billing (2019) (M.USD) | EBITDA (2019) (M.USD) | Main Source Revenue | Strategic Alternative | |

| Sonangol | 10.231 | 5.550 | Oil | Green/Renewable |

| Galp | 20.066 | 2.852 | Oil | Green/Renewable |

The various options

Sonangol can choose one of the following options or a combination of several in relation to Galp:

1-Sale of participation;

2-Reinforcement of participation;

3-Maintenance of the strategy as a financial investor;

4-Synergy in the energy transition;

5-Industrial and commercial synergies.

Let’s look at each hypothesis.

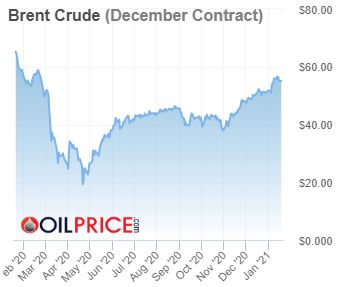

Sale of participation

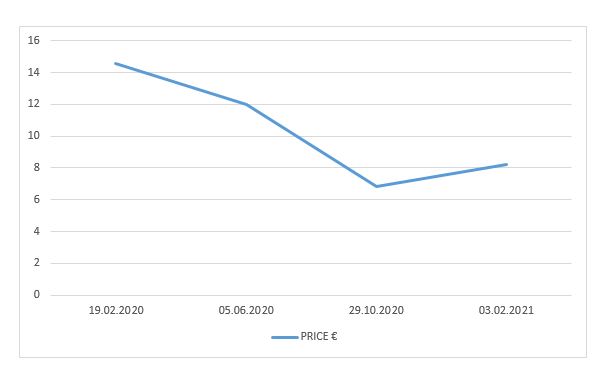

It is clear that lately the price of Galp’s shares has been discouraging. If you notice, throughout 2020 the bonds were losing value, even in October they were below € 7.00. It should be noted that this happened after the start of Covid-19, as in February 2020, the securities were being traded at around € 14.00. At this point, stock trading is slightly above € 8.00. The reality is that it is only after the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic is over that it will be possible to assess Galp’s trend market value.

Fig.nº 3. Recent evolution of Galp’s prices (source: https://www.galp.com/corp/pt/investidores/informacao-ao-acionista/acao-da-galp/desemecimento-da-acao)

Consequently, there is nothing to advise a low sale at this time.

Strengthening participation

Alternatively, Sonangol, given the low price of Galp shares, could consider strengthening its position in Galp. This would be justified as long as Sonangol had funds available for such an acquisition and saw an additional strategic interest that would lead it to have a more influential position in the company.

Maintaining the strategy as a financial investor

This has been Sonangol’s position for the past 15 years and, of course, it has borne fruit, being able to choose to maintain its posture. If we analyze Galp’s ROE (return on equity) since 2011, we see different numbers. In 2011, we had a robust number in the order of 14, 73%. In 2013, the number was around 2.86%. 2015, presented 1.91%, 2016, 2.86%. ROE in 2019 was at 6.75%, and recently in September it was negative, -8.19%[11]. This instability is important for Sonangol to evaluate its participation in Galp as it allows the Portuguese company to be qualified in terms of risk and consequent expected profitability.

This means that Sonangol will be able to convince itself that there are other more satisfactory alternatives for investing its capital and that they do not bring such large fluctuations, preferring to disinvest. We believe that if this is Sonangol’s option, this will mean that sooner than later, when the price is good, it will eventually sell the position.

Synergy in the energy transition

This is the option that seems most promising to us. With Galp already embarking on an advanced energy transition program and Sonangol wanting to take more firm steps in this direction, as indeed a good part of the large oil companies is already doing, the alliance or cooperation between Sonangol and Galp in this area, namely in solar energy, where Galp, as mentioned, has a prominent position in the Iberian Peninsula, and Sonangol comes from a country with great potential, there is a great possibility for joint action. In this sense, the possibility of creating and implementing common and ambitious projects in the area of energy transition is envisaged, providing Sonangol with the Know-How it does not have yet, and giving Galp a broad market for the development of its already designed strategy.

Industrial and commercial synergies

Obviously, the possibility of industrial and commercial synergies is immense. From oil refining at Galp’s refineries, to derivatives and shipping, in addition to using Galp’s accumulated experience in pre-salt prospecting in Brazil to open up new horizons in Angola, there are a myriad of possibilities that could be explored[12].

4. Conclusions

• The first conclusion reached through this short analysis is the need to legally reformulate the participation of Galp’s Sonangol. This should appear independently and directly in the shareholder body of the Portuguese company.

• The second conclusion is that there is a wide map of possible synergies between Sonangol and Galp, and it is strongly advised to develop them in the areas of energy transition, namely in solar energy.

[1] https://www.jornaldenegocios.pt/economia/detalhe/a-oportunidade-perdida-da-sonangol-na-galp

[2] https://www.sonangol.co.ao/Portugu%C3%AAs/GrupoSonangol/Paginas/Grupo-Sonangol.aspx

[3] https://www.galp.com/corp/pt/sobre-nos/a-galp/organizacao

[4] https://www.dw.com/pt-002/empresa-de-isabel-dos-santos-investigada-na-holanda/a-54948244

[5] https://www.galp.com/corp/pt/investidores/informacao-ao-acionista/estrutura-acionista

[6] https://www.publico.pt/2020/02/18/economia/noticia/galp-isabel-santos-nao-accionista-direta-referencia-1904644

[7] See CEO interview Sebastião Gaspar Martins in https://www.dn.pt/dinheiro/sebastiao-gaspar-martins-a-sonangol-reitera-o-seu-interesse-estrategico-em-estar-na-galp-13266123.html

[8] https://www.dinheirovivo.pt/empresas/galp-muda-ceo-com-plano-verde-e-litio-em-cima-da-mesa-13224149.html

[9] idem

[10] idem

[11] Study from https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/GLPEY/galp-energia-sgps-sa/roe

[12] We followed Celso Filipe’s suggestions closely at https://www.jornaldenegocios.pt/economia/detalhe/a-oportunidade-perdida-da-sonangol-na-galp