Angola: nova constituição, nova república?

DOCUMENTO DE REFLEXÃO

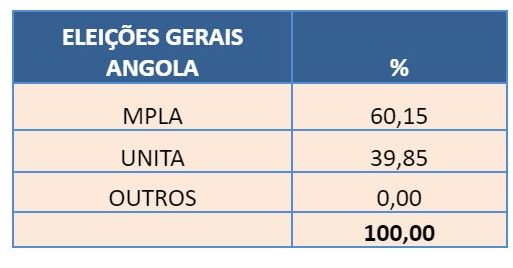

Situação atual e anocracia

Numa situação habitual, a agitação e tensão que se sentiu nos meses que precederam as eleições gerais de agosto de 2022 em Angola, teria dado lugar à normalidade e tranquilo funcionamento das instituições até ao seguinte ato eleitoral a ocorrer em 2027. No entanto, as fortes clivagens que se sentiram e aquela espécie de contenda quase global que existiu até agosto não parece diminuir, criando uma situação de constante agressão, sem um fim à vista no presente sistema. Sintoma disso é a recente entrevista dada pelo líder da oposição a um jornal português, em que declara “Nem eu, nem o partido reconhecemos a vitória do MPLA, porque sabemos que a UNITA teve mais votos. Escutámos as pessoas em todo o país. A sociedade queria que tomássemos conta das instituições, mas não quisemos o caos.”[1]

Consequentemente, de um lado, o principal partido da oposição assumiu uma política que chamaremos de “dupla via”. Tal política contesta o governo dentro das instituições, embora não lhes reconhecendo legitimidade, desafiando também as próprias instituições. A “via dupla” aceita que a oposição se faz dentro das instituições e fora delas; de certa maneira, as instituições são vistas como mais um instrumento de um projeto mais amplo de confronto com o governo. Ora é evidente que esta postura leva a um maniqueísmo difícil de gerir e coloca em causa qualquer abertura e respeitabilidade que se pretenda com o investimento. A falta de respeito pelas instituições torna tudo demasiado dependente da vontade dos decisores políticos e da conjuntura.

Do outro lado, o partido do governo sente-se embaraçado em levar avante as suas anunciadas reformas, é como se o partido não fosse um, mas dois partidos. Uma massa partidária está insatisfeita com as mudanças propostas, queria que João Lourenço fosse apenas um gestor mais hábil do que José Eduardo dos Santos, mas não que introduzisse reformas de fundo, outro sector pretende que sejam tomadas efetivas reformas e sente-se incomodado com a eventual lentidão dessas reformas. Têm a noção que sem um profundo processo reformista, Angola se pode transformar num Estado sem futuro.

Há assim uma forte instabilidade, por razões diversas, nos partidos que formam a sustentação do sistema político. A Assembleia Nacional não parece ser uma câmara deliberativa do sentir da nação, mas um mero palco duma disputa mais alargada, tornando-se num meio e não num fim, retirando-lhe o peso soberano que lhe seria inerente. Com um registo mais atemorizador surge a justiça. Aquele que é o pilar básico de um Estado Democrático de Direito, oferece mais dúvidas do que certezas. No combate à corrupção, com honrosas exceções, o sistema judicial tem-se pautado pela ineficiência e lentidão, não se percebendo já para onde caminha esse programa estruturante do Estado. Como já escrevemos: “É verdade que o desenho do Tribunal Supremo contido na Constituição de 2010 ajuda à sua disfuncionalidade. Na verdade, o legislador constitucional angolano quis fazer um tribunal seguindo o modelo da Supreme Court norte-americana enxertado num sistema judicial de tipo romano-germânico, isto é, português. Ora um tribunal de topo no sistema judicial português, alemão ou francês, nada tem a ver com um tribunal de topo num sistema anglo-americano. São conceitos e estruturas judiciais diferentes. O que se pede a um tribunal supremo norte-americano não é o que se pede a um supremo tribunal português. No primeiro caso, apenas grandes e inovadoras questões de direito lá chegam. É já uma espécie de tribunal de reflexão, enquanto, no segundo caso-romano-germânico- o supremo funciona como última instância de recurso para quase todos os casos judiciais. Todavia em Angola, pensou-se um tribunal à americana para funcionar à portuguesa. Portanto, uma estrutura leve e que apenas se dedicava a um pequeno número de processos teve de se defrontar com a tarefa de ser um tribunal habitual de recurso para uma miríade de casos. Isso só podia dar mau resultado, como deu. Além da disfuncionalidade do desenho constitucional, tem-se entendido que os juízes do Tribunal Supremo não têm a preparação adequada para lidar com as complexidades do crime económico-financeiro, não tendo ao longo da sua carreira deparado com essas questões ao nível sofisticado a que têm estado a aparecer, o que tem levado a algumas decisões muito criticadas e a grande mora processual. Iniciando o país simultaneamente uma fase de grande apelo ao investimento estrangeiro, bem como apostando na luta contra a corrupção, é bem de ver que um tribunal mal desenhado e pensado para outros tempos tem de ser reformado e remodelado.”[2]

No seu geral, a justiça não tem oferecido garantias de celeridade e imparcialidade técnica, e os seus atores têm tido uma tendência surpreendente para se envolverem em escândalos consecutivos.

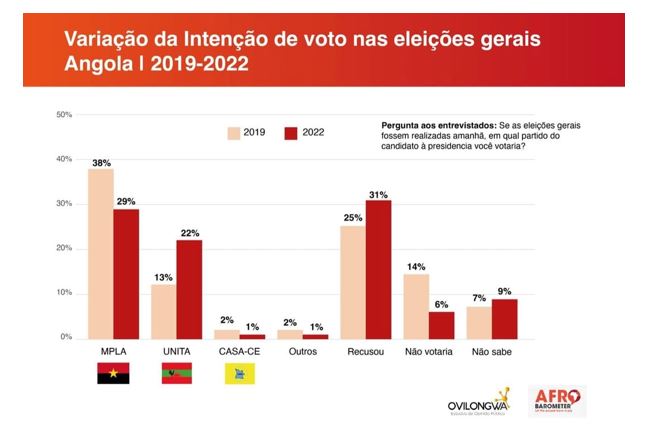

Por parte da população começa a haver uma ideia tímida, mas discutida em vários fora, que as atuais instituições e partidos políticos foram concebidos para um ambiente de guerra e confronto, estando essas características no seu âmago, e, por isso, não estão aptos a lidar com uma nova Angola, em que os objetivos centrais sejam o desenvolvimento e o bem-estar da população. Quer isto dizer que se considera que os “velhos” partidos já não correspondem aos desejos e interesses da população, não oferecendo soluções consistentes e apelativas. A taxa de abstenção das últimas eleições gerais (54%) é espelho dessa situação.

Uma Assembleia Nacional que se transformou em mero instrumento-eco de poder e contrapoder, uma justiça inepta e um sistema partidário anacrónico, definem o presente sistema institucional angolano.

Toda esta situação, um pouco difusa, mas cujos sinais abundam, podem tornar o país numa anocracia. O que é uma anocracia? A anocracia vem sendo definida como um regime instável que combina elementos de autoritarismo e democracia. A anocracia tem um desenvolvimento incompleto de mecanismos de dissensão e consensualização e associa-se a uma permanente agitação ou ingovernabilidade, que dificultam o processo político[3]. A existência duma situação anocrática aumenta a probabilidade [4] de uma guerra civil. Colocando o tema de outra forma, o que procura interrogar é se a situação angolana se apresenta inerentemente instável e pode redundar numa guerra civil?

A resposta é simples, embora tendo duas partes. Não, Angola não vive ainda uma situação de anocracia. Contudo, são exigíveis medidas estruturantes que ultrapassem os presentes bloqueios e insatisfações.

Nova Constituição e Nova República

É necessário criar um Estado ágil, com instituições respeitadas, uma administração pública funcional e uma economia de mercado com atores livres e competitivos, tudo contribuindo para o progresso e bem-estar da população. As estruturas herdadas do colonialismo e das guerras têm de ser transformadas e trocadas por estruturas da modernidade e desenvolvimento, tendo em conta a cultura e história de Angola.

É fundamental um novo ciclo histórico com uma nova estrutura.

A primeira medida é estabelecer uma nova constituição. A atual constituição de 2010 não é consensual e, até certo ponto, é um equívoco jurídico desenhado para agradar aos desejos pessoais de José Eduardo dos Santos. Fundamental será propor uma nova constituição mais angolana e mais protetora das instituições, que marque um recomeço. Entende-se que essa nova Constituição deveria abordar aspetos tão diferentes como a possibilidade de eleição separada (direta ou indireta) do Presidente da República, conferindo-lhe uma legitimidade própria e garantindo que o Presidente se apresente como um líder nacional e não um líder partidário, a criação de uma segunda câmara legislativa composta pelas autoridades tradicionais (permitindo a introdução de vozes diferentes e plurais no processo legislativo, recuperando a cultura africana), a introdução de mecanismos de democracia militante como tem a lei fundamental alemã (como Karl Loewenstein[5] escreveu a democracia deveria ser capaz de resistir àqueles agentes políticos que utilizam instrumentos democráticos para assegurar o triunfo de projetos totalitários ou autoritários de poder, isto significando, que a constituição tem de conter mecanismos de defesa e repressão das tentativas de derrube do regime constitucional, o que agora não existe com força suficiente na constituição angolana). Obviamente, que a reformulação do poder judicial, a mudança da simbologia da república, seriam outros aspetos desta nova constituição.

Não basta uma mudança constitucional sem se tratar da organização e administração do Estado. Também aqui o projeto de transformação tem de ser abrangente e procurar-se a libertação dos modelos coloniais e marxistas, introduzindo uma administração pública adequada aos novos tempos. Exemplos podem vir da Ásia, como a China e Singapura[6], ou dos países vizinhos como o Botswana ou a África do Sul. O paradigma tem de ser uma administração baseada no mérito, assente na eficácia e no serviço à população. Naturalmente, que tal implica o fim da influência clientelista na administração, a desconcentração com autonomia e capacidade de tomada de decisão, uma forma completamente nova de ver o procedimento administrativo, não como um conjunto de regras, mas um conjunto de boas práticas e objetivos vocacionados para o bem comum e eficácia.

É evidente que apenas se deixam aqui alguns tópicos sobre as mudanças estruturais aconselháveis, segundo a nossa perspetiva, para transformar Angola num Estado moderno e próspero.

[1] Adalberto da Costa Júnior, entrevista ao Nascer do Sol, 20-01-23

[2] CEDESA (2022). A necessária reforma do Tribunal Supremo em Angola, https://www.cedesa.pt/2022/11/24/a-necessaria-reforma-do-tribunal-supremo-em-angola/

[3] Jennifer Gandhi e James Vreeland (2008). “Political Institutions and Civil War: Unpacking Anocracy”. Journal of Conflict Solutions. 52 (3): 401–425; Patrick Regan and Sam Bell, Sam (2010). “Changing Lanes or Stuck in the Middle: Why Are Anocracies More Prone to Civil Wars?”. Political Science Quarterly. 63 (4): 747–759.

[4] Patrick Regan and Sam Bell, Sam (2010). “Changing Lanes or Stuck in the Middle: Why Are Anocracies More Prone to Civil Wars?”. Political Science Quarterly. 63 (4): 747–759.

[5] Karl Loewenstein (1937) Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights, in: American Political Science Review 31.

[6] M. Shamsul Haque (2009), Public Administration and Public Governance in Singapore in Pan Suk Kim, ed., Public Administration and Public Governance in ASEAN Member Countries and Korea. Seoul: Daeyoung Moonhwasa Publishing Company, 2009. pp.246-271.